Men of the House: Modes of Masculinity in The Godfather

By Janani Hariharan

In The Godfather, director Francis Ford Coppola introduces the lead character Michael Corleone in the most curious of ways: almost thirteen minutes after the film has begun, Michael walks into his sister’s extravagant wedding, wearing a full Marines Corps uniform with a non-Italian-American woman on his arm.

This choice on Michael’s part, and on the part of Coppola, signals how The Godfather — though produced in the early 1970s — is a film that reflects on the mid-1940s, a time when masculinity was being redefined in the wake of the Second World War. Historian Corinna Peniston-Bird argues that during the war, “opportunities for contraction, transformation and resistance were limited. Men did not have a choice whether to confirm or reject hegemonic [military] masculinity.” But what happened once the war ended, when men had to use their bodies outside of war? What happened when decorated war heroes like Michael had to come home and redefine their manhood without wartime’s existing framework?

This problem is tackled in The Godfather through Michael but extends to every man in his family. The Godfather dramatizes this crisis of masculinity through male characters’ interactions with other men. While Vito uses restrained movements to exert influence, Sonny’s big, brash, impulsive actions take up space. Michael, meanwhile, takes a page out of both their books, using his intelligence and audacity to command authority. Insofar as the film equates masculinity with power, these important male characters in the film use their bodies in different ways to secure their patriarchal positions at the head of the family.

***

Vito Corleone controls his movements impeccably, using his body in only the most understated of ways to convey a sense of omnipotent authority over other men. This becomes evident as soon as the movie begins: the first time we as viewers lay eyes on any part of Vito, the camera faces Bonasera from over Vito’s shoulder. Bonasera, sitting on the other side of Vito’s desk, begins to sob at the plight of his daughter’s suffering. We see not a commanding body towering over Bonasera but an out-of-focus hand in the foreground, gesturing to a capo to bring Bonasera a drink in consolation, which he gratefully accepts.

With just the use of one out-of-focus hand, the film situates Vito’s authority in methodical action and institutional relevance. His is a masculinity characterized by the deference and obedience of other powerful men — a masculinity that doesn’t need to exert power actively because the institution he has built on his own terms does it for him. Soon after the camera cuts to face Vito, we see him petting a small cat on his lap as he discusses matters of life or death with Bonasera. The cat, sprawled on his lap, luxuriates in his attention and infuses a playful energy into an otherwise dark and brooding room. Past critics have pointed to the cat as representative of hidden claws under Vito’s subdued façade. To me, however, a subtler detail stands out, particularly when Bonasera makes the grave mistake of asking Vito, “How much shall I pay you?” Vito immediately looks up at him from the corner of his eyes, affronted, and stops playing with the cat. He puts the cat on the table as if to mean serious business, stands up, and calmly confronts Bonasera about his infraction: “Bonasera, Bonasera. What have I done to make you treat me so disrespectfully?”

The cat in Vito’s hands is a symbol of the judicious way in which he wields power: he plays with the cat and gives it what it wants until he decides playtime is over. The Don giveth, and the Don taketh away, so to speak. These first few scenes illustrate what I would call Vito’s calculated gentleness: his body language is characterized by restraint, which highlights the authority he draws from simply being the head of the family and being revered and feared by so many.

Of course, Vito’s authority changes after he steps down from his position as the copo dei capi. Vito becomes more of a family man, indulging in wine and time with his grandchildren. In an uncharacteristically tender moment toward the end of the film, we see Vito playing with his grandson in the garden. He presses an orange peel against his teeth to scare the child and lets him spray him with a water gun as they run around through the orange plants.

Poignantly, this is when his body gives out and he passes away. “I spend my life trying not to be careless,” Vito had admitted to Michael just moments before the film cuts to the garden scene. You would think that being a Mafioso is more life-threatening than being a grandfather, so it seems particularly biting that during his most unprotected moment in the film, he dies. Vito’s masculinity and power rest on the foundation of the institution he has built; when he finally moves without formal restraint, his vulnerability is not allowed to last. Within the scope of being a being a don, tenderness — when it’s not calculated — becomes weakness.

***

This weakness becomes apparent after an attempt is made on Vito’s life by a rival family, and the film offers up his oldest son, Sonny, as a solution to this newly created vacuum of power. But if Vito spends his life trying not to be careless, Sonny is a man who spends his life doing the complete opposite. Brash and impulsive, Sonny wields his body in intensely physical, violent ways; he asserts a hypermasculinity in relation to those around him, men and women alike. During Connie’s wedding, Sonny flirts with the maid of honor as his wife Sandra sits at another table. Soon after, we see Sonny and the bridesmaid in a bathroom having rough sex up against a door. Tom Hagen goes looking for him at Vito’s request and knocks on the door. “Sonny, are you in there? … the old man wants to see you,” Tom calls from the outside. “Yeah, one minute,” Sonny responds, before continuing with his pursuit.

If Vito maintains his masculinity through restraint in order to keep the family in power, Sonny asserts his through reckless self-indulgence, prioritizing his own needs and desires over those of the family. A particularly telling moment later on in the film illustrates this difference of worldview between father and son. In a meeting about the possible growth of the drug trade in their area, Vito and Sonny learn from a fellow Mafioso that the Tattaglia family would be willing to work together to ensure the Corleone family’s security. Sonny, immediately interested, butts into the conversation: “You’re telling me that the Tattaglias would guarantee our invest—” But Vito does not allow him to finish. “Wait a minute,” Vito tells Sonny, as he looks back at him, irked and disappointed, and proceeds to elegantly divert the conversation away from the infraction.

After the meeting ends, Vito tells Sonny to stay behind and reproaches him: “Santino … what’s the matter with you? I think your brain is going soft from all that comedy you’re playing with that young girl. Never tell anybody outside the family what you’re thinking again.” Sonny, like a disobedient child who refuses to listen, looks away and rolls his eyes at the scolding. Through this interaction, we see that Sonny’s intelligence and competence as a man and a leader is frustrated by his impulsive desire to disobey the configuration of norms and codes as set by Vito. His refusal to practice restraint and judiciousness in making decisions upsets Vito, and it is ultimately what leads to his downfall.

Yet Sonny loves his family as fiercely as he indulges in his own whims and fancies — and as the film progresses, these two passions create a recipe for disaster. Sonny finds his sister Connie with bruises all over her face, ostensibly because she had been abused by her husband Carlo. “Sonny, please don’t do anything. Please don’t do anything,” Connie pleads, recognizing where Sonny’s mind would immediately go. “What am I going to do? Make that baby an orphan before he’s born?” Sonny says as he holds her. In the scene that immediately follows, Sonny jumps out of a car with a baseball bat and chases Carlo down. “If you touch my sister again, I’ll kill you,” Sonny says through gritted teeth, after having beaten him to a pulp.

While it may seem like a justified retribution — a black eye for a black eye — it is this hotheadedness that triggers Sonny’s downfall. After another violent altercation between Connie and Carlo, Sonny receives a call from Connie. “You wait right there,” he says, and jumps into a car and drives off angrily, despite pleas from Tom to stop or at least slow down. “Go after him, go on!” Tom tells other members of the family, and they get into a car to follow him. Sonny ultimately drives off to his demise as he is ambushed at a tollbooth by machine gunfire, in a set-up orchestrated by enemies of the family with the help of Carlo.

If Sonny had not been so quick to attack Carlo after the first incident, he may have never made an enemy out of Carlo and would not have met such a gruesome and sudden death. Minutes after the assailants drive away, Tom’s men arrive at the scene only to find Sonny lying dead in the middle of the road. At the very least, if Sonny had waited for others to join him before he drove away to confront Carlo, he would have had some form of reinforcement during the ambush. Unlike Vito, Sonny is neither calculated nor gentle, relying on brutish force and carnal instinct to use his body and exert power. His masculinity ultimately proves to be an unfeasible solution to the vacuum of power in the wake of Vito’s attack.

***

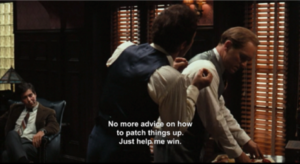

Sonny’s death leaves his younger brother, Michael, as the most viable option to take the helm of the Corleone family. If Vito’s quiet authority and Sonny’s careless impulsiveness occupy opposite ends of the spectrum of masculinity presented in the film, Michael’s masculinity lies squarely in the middle. He is intelligent and collected but unforgiving: he has the tact of his father and the audacity of his brother. A telling difference between Sonny’s and Michael’s body language is highlighted during the two brothers’ meeting with Clemenza, Tom, and Tessio, as the five discuss how to handle Sollozzo’s request to discuss a truce. Sonny unsurprisingly raises his voice at the idea of Sollozzo’s proposition, pacing the room aggressively and yelling at those who suggest hearing Sollozzo out. “No more meetings, no more discussions, no more Sollozzo tricks,” Sonny yells, towering over Tom. “Do me a favor, Tom, no more advice on how to patch things up. Just help me win.” Michael, on the other hand, sits stoically on a plush chair, watching the scene unfold. After a brief moment of silence, Michael enters into the conversation. “We can’t wait,” he says calmly, remaining seated. “I don’t care what Sollozzo says about a deal, he’s going to kill Pop. That’s it.”

Interestingly, Sonny and Michael want the same thing: they both think it’s wiser to strike now rather than give Sollozzo the benefit of the doubt. This is indicative of their potential to both be sound leaders. However, what Sonny articulates via artless aggression, Michael expresses in a methodical plan of action. “They want to have a meeting with me, right? … Let’s set the meeting,” Michael says, as he goes on to detail how they will orchestrate the ambush and dodge any possible retaliation.

We might see both Vito and Michael as self-made men — or self-made Dons — though they take different routes to that same destination. While Vito built the institution of the Corleone family from the ground-up, Michael comes of age over the course of the film and makes himself into a man by virtue of avenging an attempt on his father’s life. We later see that Michael successfully carries out the plan for the Corleone family, unflinchingly putting bullets in Sollozzo’s and Captain McCluskey’s heads and ending the threat to this father’s life. Insofar as Vito possesses a calculated gentleness and Sonny does not, Michael learns from their shortcomings to realize a calculated ruthlessness. He is a man who does not strike unless it is absolutely necessary — but does not hesitate to get his hands dirty when he must.

Michael’s newfound, calculated ruthlessness is powerfully evoked in the movie’s bloody climax, in which the camera cuts between the baptism of his godson and the assassinations of his rivals. But Michael’s metamorphosis is even more strikingly dramatized in a scene soon after, when Michael confronts Carlo about his complicity in Sonny’s murder. “Sit down,” he tells Carlo, as he pulls up a chair and takes a seat next to him. He pats Carlo on the shoulder and calmly reassures him: “Don’t be afraid. … Do you think I’d make my sister a widow?” Michael tells Carlo that he will have to leave for Las Vegas and hands him a plane ticket. “Only don’t tell me you’re innocent because it insults my intelligence. … Now, who approached you?” Michael asks. When Carlo finally admits to his involvement, Michael directs him to a car that is supposed to take him to an airport. Clemenza, sitting in the backseat, garrotes Carlo to his death, as Michael watches from the outside.

For all the talk that we hear of Vito “taking care of business” toward the beginning of the film, we never once see him personally enact violence or be in the vicinity of it. Michael, on the other hand, both tactfully extracts a confession and also watches his brother-in-law lose his life at his own order, without so much as a flinch. The film establishes Michael’s masculinity relationally through the men that came before him: he learns from his father’s distaste for violence and his brother’s carelessness to become a true, successful copo dei capi of the Corlene family.

Michael’s consolidation of power proves to be a fitting end to the first installment of The Godfather trilogy, which is primarily interested in charting the jostle for power between and within families to establish a new socio-political hierarchy within the organized crime circuit in mid-1940s America. In the post-war context, men grappled with how to express their masculinity and assert their dominance outside the battlefield.

The film encapsulates this struggle by moving through two different modes of masculinity — through Vito and Sonny — before settling on the only viable option in Michael, whose calculated ruthlessness secures the survival and prosperity of the family. The other Dons have been vanquished, and there are no other characters within the family who might take its helm: the film underscores how Fredo’s feebleness and lack of intelligence and Tom’s non-Sicilian heritage effectively take them out of consideration for the leadership of the family, while the women of the film are shut out of that form of power entirely. Michael stands alone, unchallenged — his character having “successfully” resolved the film’s complex exploration of the relationship between gender and power in the post-war era.

Janani Hariharan (Cal ’18) is a senior studying Business Administration and English. She may have been much too young when she first watched The Godfather twelve years ago, but she is using this project to help her recover as she continues to explore the implications of gender and its performance in her favorite works.

Work Cited

Linsey Robb and Juliette Pattinson, Men, Masculinities and Male Culture in the Second World War (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).