Hemmed In: Kay Adams and Her Changing Fashions

By Emma Hager

Anna Hill Johnstone, the costume designer for The Godfather, knew how to make male antiheroes into fashion icons. In the mid-’50s, she outfitted the cool of Marlon Brando in On the Waterfront and of James Dean in East of Eden. On The Godfather—for which she received an Oscar nomination—she turned Al Pacino (dubbed “the midget” by producer Robert Evans) into an icon of slow-burning glamour with his dark three-piece suits and his tilted homburg hat.

Given that women speak all too rarely in the film, it’s especially important that we dwell on how their clothes speak for them.

What is often gravely overlooked is how much Johnstone’s genius—meticulous, deliberate, pointed—shaped the women’s fashions in the film. This is not surprising given how much the film trades in the currency of masculinity. Women in the film—or at least the idea of them—act as magnets of male ambition, motive, and desire. From a symbolic standpoint, that’s a powerful position to be in, but it’s also a problem that The Godfather’s women serve mostly as conduits for a story about men’s feuds and men’s business.

Given that women speak all too rarely in the film, it’s especially important that we dwell on how their clothes speak for them. We need to pay attention, when we can, to the pouf of a sleeve or the hem of a dress; they offer a lexicon cut from different cloth, whose words are quite revealing.

Corleones, meet Kay

Our first glimpse of Kay Adams (Diane Keaton) is from behind. She’s just arrived at Connie and Carlo’s wedding with her beau, Michael Corleone, a Marine back from the War. Michael, in a display of patriotism or of rote performance, wears his brown and boxy uniform. It’s well-tailored and simple—stoic, even, what with its precise hems.

Our first glimpse of Kay Adams (Diane Keaton) is from behind. She’s just arrived at Connie and Carlo’s wedding with her beau, Michael Corleone, a Marine back from the War. Michael, in a display of patriotism or of rote performance, wears his brown and boxy uniform. It’s well-tailored and simple—stoic, even, what with its precise hems.

Next to Kay, Michael and his uniform nearly disappear, swallowed by the aimless enormity of her gown. Because it’s orange-y-red with polka dots, parachuted at the sleeves, and generously petticoated, the gown would swallow Kay entirely, too, if it weren’t for its fitted waist. The burgundy belt is there as if to say there’s a person, here, underneath it all.

Kay has not dressed inappropriately for the wedding; there’s plenty of lace and tulle and crinoline to go around. Corleone women and guests jaunt about the scene, too, in garments of similar volume, yet the mostly pinks and otherwise pastels of their dresses offset Kay’s red look entirely. If all the other women look similarly elaborate and cartoonish, it’s in a different way. They’re like cakes, tiered and frothy, and Kay the sole tablecloth upon which to place them. This is an outdoor ceremony, after all, and her large look enough to be a picnicking surface.

It would be easy to dismiss this sartorial difference as one of mere taste; one might conjecture that Kay has chosen her dress from a different page of the Saks catalog. But this is a film whose aesthetic choices are excruciatingly deliberate, reflecting its grave polarities (good vs. bad) and ultimatums (life vs. death). Matters of taste are also ones of allegiance. And so it is through Kay’s laughably floppy gown, what with all its unwitting kitsch, that we’re first encouraged to be skeptical of the viability of Kay’s position in the family. Sure, the dress has an Americana charm, recalling Sunday drives and Wonder Bread, and may suggest an aspirational innocence, or a WASP-y posture, but already the contrasts are too stark to be easily resolved.

There will be no seamless synthesis into the family, nor will Kay ever be a raw and ready object of desire. Her beauty is sensible, lucrative; it frames her New Hampshire, Baptist upbringing, to which Michael turns, initially, as a means of Americanizing his life.

The Apollonia Distraction

To be naturalized, in some ways, through Kay, is a decent goal. But there’s still the immediate and irresistible allure of Apollonia Vitelli (Simonetta Stefanelli), Michael’s young and virginal bride whom he meets while hiding in Sicily. Her beauty is bewitching, her eyes rich and mysterious, her lips plush and pink. And Michael, upon seeing Apollonia for the first time as she comes traipsing up a dusty trail, goes still; he has been, in the words of his bodyguard, “struck by a thunderbolt.”

Indeed, our first glimpse of Apollonia — perhaps because it is also Michael’s — is a carnal yet unfussy one. Her burgundy dress, knee-length and loose but still generous to her feminine contours, takes up the movement of the wind. Its lightness means it could blow up, or off, at any moment, like she’s something to be undone. Unlike Kay’s saccharine and synthetic wedding ensemble, Apollonia’s dress, with its airiness and earthen tone, complement the browns and reds of the scorched Sicilian landscape. She’s of the earth, pure, and a desire for her is only natural. Michael has returned to his family’s point of origin, and the relative ease with which he dons the ubiquitous newsboy hat and flowy, peasant blouse — as opposed to his stiffness in the stiff Marines suit — finds its assuring companion in the nonchalance of Apollonia’s garment.

Indeed, our first glimpse of Apollonia — perhaps because it is also Michael’s — is a carnal yet unfussy one. Her burgundy dress, knee-length and loose but still generous to her feminine contours, takes up the movement of the wind. Its lightness means it could blow up, or off, at any moment, like she’s something to be undone. Unlike Kay’s saccharine and synthetic wedding ensemble, Apollonia’s dress, with its airiness and earthen tone, complement the browns and reds of the scorched Sicilian landscape. She’s of the earth, pure, and a desire for her is only natural. Michael has returned to his family’s point of origin, and the relative ease with which he dons the ubiquitous newsboy hat and flowy, peasant blouse — as opposed to his stiffness in the stiff Marines suit — finds its assuring companion in the nonchalance of Apollonia’s garment.

To my mind, if Kay recalls the sort of competent women played by the actress Theresa Wright in the postwar period, then Apollonia is a sort of Lolita figure. She’s Michael’s own kind of Nabokovian nymphet.

Nowhere in the film are we confronted with the archetypal contrasts of these women more than in an abrupt scene cut from one woman to the next, which cuts across geography and cloth. We start, in one moment, with an intimate scene between Michael and Apollonia. It’s the evening of their wedding, which occurred earlier in the day, and they appear now in white in their bedroom. Michael is in an unbuttoned dress shirt; Apollonia in an ivory negligee. He inches toward her. And while she’s initially hesitant with all the qualms of inexperience, the pencil-thin straps of her negligee fall away from her shoulders. They kiss.

Nowhere in the film are we confronted with the archetypal contrasts of these women more than in an abrupt scene cut from one woman to the next, which cuts across geography and cloth. We start, in one moment, with an intimate scene between Michael and Apollonia. It’s the evening of their wedding, which occurred earlier in the day, and they appear now in white in their bedroom. Michael is in an unbuttoned dress shirt; Apollonia in an ivory negligee. He inches toward her. And while she’s initially hesitant with all the qualms of inexperience, the pencil-thin straps of her negligee fall away from her shoulders. They kiss.

Back in America, Kay Can’t Get Through

The camera cuts abruptly, back to America, where Kay exits a red and yellow taxi outside the Corleone compound. She’s on a mission. She wants to get in touch with Michael, though Tom Hagen (Robert Duvall), who meets her at the compound gates, refuses to pass on her letter to for fear of being further implicated in Michael’s hiding.

The camera cuts abruptly, back to America, where Kay exits a red and yellow taxi outside the Corleone compound. She’s on a mission. She wants to get in touch with Michael, though Tom Hagen (Robert Duvall), who meets her at the compound gates, refuses to pass on her letter to for fear of being further implicated in Michael’s hiding.

Kay’s ensemble here is signature to her. It sticks to the register of her previous looks: she wears a rounded, red coat and a matching hat. The tablecloth-like quality of her first look is preserved through the polka-dotted blouse. But when it’s set against the backdrop of the preceding scene, which is doused in Apollonia’s wanton energy, the outfit choice is made jarring. The tailoring is sure and strong, but the coat’s ketchup-like color is almost droll. This is not the crimson of desire; she must pursue Michael, find him out, though he retreats to the bosom of Apollonia.

Assuming, Subsuming

Eventually, Michael returns to the United States; Apollonia dies in an accident. Lust, like happiness, is mostly fleeting. There’s business to do and an American posture to assume again. Kay is, as mentioned, integral to this Americanization. It’s fitting that their first reunion, since Michael’s Sicily tenure, occurs outside the school where Kay is employed.

Michael emerges from a smooth, black car in a smooth, black overcoat; Kay struggles to keep the schoolchildren in line. She’s got on a trench coat — just more beige than a sea-foam green — a knitted skirt set, brown loafers and a string of pearls. She’s styled her hair into a bouffant, and it’s the most pronounced and animated aspect of her new, otherwise demure look. Gone are the tomato reds and roadside dining patterns.

Michael emerges from a smooth, black car in a smooth, black overcoat; Kay struggles to keep the schoolchildren in line. She’s got on a trench coat — just more beige than a sea-foam green — a knitted skirt set, brown loafers and a string of pearls. She’s styled her hair into a bouffant, and it’s the most pronounced and animated aspect of her new, otherwise demure look. Gone are the tomato reds and roadside dining patterns.

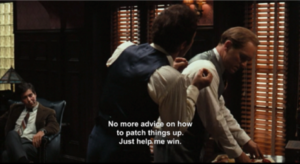

While Kay’s power, to the extent we can conceive it as such, has never been a sexual one, this outfit helps to eradicate all previous hints of vibrance. Kay’s function is more pragmatically strict than ever, and Michael’s marriage proposal to her is more an admission of defeat—of how he’s working in a mode of ‘damage control’—than it is a demonstrated commitment to some ineffable bond. Kay professes it’s “too late” when Michael expresses his tenderness in the form of an addendum: “and I love you.” Only it’s not about that, of course, and anything beyond the transactional is muted — just like the green of Kay’s coat.

The Shadow of Doubt

The film closes with a closed door. The last shot is of a defeated-looking Kay, who stands in the frame of Michael’s office, looking longingly into its interior. Inside, there’s a world to which she’s not welcome. Kay cannot stay, and eventually one mafioso shuts the door on her; the shadow is increasingly cast upon her face until we get only her vague outline.

The film closes with a closed door. The last shot is of a defeated-looking Kay, who stands in the frame of Michael’s office, looking longingly into its interior. Inside, there’s a world to which she’s not welcome. Kay cannot stay, and eventually one mafioso shuts the door on her; the shadow is increasingly cast upon her face until we get only her vague outline.

It’s a peculiar and compelling choice for an ending since it privileges the female as its object, but is explicitly exclusionary in its shutting the door on her. But perhaps this makes perfect sense for Kay, and more so when we consider her “purpose.” Michael has fully assumed his role; Kay has given him children. A transaction complete. A door closed.

In her final outfit, Kay’s features do not stand out, and it’s as if she has faded into the role of herself.

As the men buckle down for business , we see Kay buttoned up in a golden-beige shirtdress. It’s a fitted garment, for the most part, with only a slight flare of the skirt rendering any semblance to the comic largeness of her first look. Her hair has the same champagne glow as the fabric. Kay’s features do not stand out, then, and it’s as if she has faded into the role of herself.

Uncertainty and doubt invade the last shot, take over Kay’s face, but at least the lines of her dress are stiff and sure. A domestic armor.

Emma Hager (‘18) is a senior at the University of California, Berkeley, where she studies English literature. Regrettably, she still has yet to read Middlemarch.

We hear a simultaneous scream, made more unsettling by its deepness, and by our awareness that it comes from a grown man who cannot suppress the anguish of his pain. And just like that, without warning, we are ejected at once from the scene’s mellow, easygoing tempo to one of fast-paced horror. By the time the garrote is placed around Brasi’s throat by an unknown assailant, we want Luca to overpower him, to use brute strength or even his gun to turn the outcome around. Ultimately, we just want his suffering to stop.

We hear a simultaneous scream, made more unsettling by its deepness, and by our awareness that it comes from a grown man who cannot suppress the anguish of his pain. And just like that, without warning, we are ejected at once from the scene’s mellow, easygoing tempo to one of fast-paced horror. By the time the garrote is placed around Brasi’s throat by an unknown assailant, we want Luca to overpower him, to use brute strength or even his gun to turn the outcome around. Ultimately, we just want his suffering to stop.

Early in the opening wedding scene of The Godfather, a photographer lines up the Corleone family, preparing a family photo to solemnize the marriage of Constanzia, or Connie, Corleone to Carlo Rizzi. Yet Vito Corleone, the Don of this Sicilian family, notes his youngest son’s absence and so stops the shot from being taken: “We’re not taking the picture without Michael.” A picture is forever, and Vito—the center of the family, and with an especially soft spot for his son Michael—insists that all must be present and all must be willing to play their part. What Vito has created through the Corleone family is represented in its purest and most picturesque form by Connie’s wedding, which is huge, vibrant, and cheerful.

Early in the opening wedding scene of The Godfather, a photographer lines up the Corleone family, preparing a family photo to solemnize the marriage of Constanzia, or Connie, Corleone to Carlo Rizzi. Yet Vito Corleone, the Don of this Sicilian family, notes his youngest son’s absence and so stops the shot from being taken: “We’re not taking the picture without Michael.” A picture is forever, and Vito—the center of the family, and with an especially soft spot for his son Michael—insists that all must be present and all must be willing to play their part. What Vito has created through the Corleone family is represented in its purest and most picturesque form by Connie’s wedding, which is huge, vibrant, and cheerful. In the first shot following Vito’s dealings with Amerigo Bonasera, we glimpse the throng that has assembled for the event: though a tree covers half of the crowd, there are still dozens of visible people milling around, and by placing the camera far from the event, the individual people become a blur and turn into one huge sea of costumed bodies. The image suggests how, to the Corleones, a family should function: though the individuals that make up the larger family business are essential to its workings, they are all under the guise of one group and so are united by that group. Even with a sizable attendance already inside the estate, people can be seen still walking into the courtyard. Everyone, from tiny toddlers to their aging grandparents, must come and pay respects to Connie in this momentous event.

In the first shot following Vito’s dealings with Amerigo Bonasera, we glimpse the throng that has assembled for the event: though a tree covers half of the crowd, there are still dozens of visible people milling around, and by placing the camera far from the event, the individual people become a blur and turn into one huge sea of costumed bodies. The image suggests how, to the Corleones, a family should function: though the individuals that make up the larger family business are essential to its workings, they are all under the guise of one group and so are united by that group. Even with a sizable attendance already inside the estate, people can be seen still walking into the courtyard. Everyone, from tiny toddlers to their aging grandparents, must come and pay respects to Connie in this momentous event. Yet Vito is not just a man who spends a lot of money to make his daughter’s wedding a great celebration; he’s the sort of father who actively shows his care with that money by partaking in the festivities, spending time with his family throughout despite his ongoing business deals behind the scenes. This scene fills the wedding with his attention and care as he dances with his wife in the midst of the crowd. Smiles on their faces, the couple waltz as Vito makes an inaudible comment to his wife that conveys the couple’s agreeable intimacy.

Yet Vito is not just a man who spends a lot of money to make his daughter’s wedding a great celebration; he’s the sort of father who actively shows his care with that money by partaking in the festivities, spending time with his family throughout despite his ongoing business deals behind the scenes. This scene fills the wedding with his attention and care as he dances with his wife in the midst of the crowd. Smiles on their faces, the couple waltz as Vito makes an inaudible comment to his wife that conveys the couple’s agreeable intimacy. This scene is mirrored again at the end of the wedding: Vito leads his daughter through the crowd of clapping attendees, clutching her hand tightly. Holding hands is a sign of affection often seen between a parent and a young child, and in this context the meaning is still valid—perhaps even more so due to Connie’s older age and the likelihood that they no longer are so physically close. As Vito carefully lays his hand on her waist and they begin to waltz, Connie speaks inaudibly to him, causing them both to smile. When the scene cuts to a shot farther away from the two, Connie hugs him tightly as they continue their waltz. This increased physical affection suggests their own emotional intimacy, which they unabashedly display on stage.

This scene is mirrored again at the end of the wedding: Vito leads his daughter through the crowd of clapping attendees, clutching her hand tightly. Holding hands is a sign of affection often seen between a parent and a young child, and in this context the meaning is still valid—perhaps even more so due to Connie’s older age and the likelihood that they no longer are so physically close. As Vito carefully lays his hand on her waist and they begin to waltz, Connie speaks inaudibly to him, causing them both to smile. When the scene cuts to a shot farther away from the two, Connie hugs him tightly as they continue their waltz. This increased physical affection suggests their own emotional intimacy, which they unabashedly display on stage. Instead of greeting Michael with care and love—as Tom Hagen does when he first sees Michael, and as an older brother should do after not having seen his younger brother in quite some time—Fredo flicks the back of Michael’s head. While this gesture suggests a kind of playful intimacy, it underscores Fredo’s immaturity and inability to socialize with people in a more dignified way. The blocking of the action in the scene—with Fredo kneeling between Michael and Kay—also conveys his awkwardness and divisiveness. Michael’s act of bringing Kay to the wedding shows his devotion to her and telegraphs that one day, they too might get married. When Fredo sits between them, he separates the two and effectively disrupts the natural state of the couple.

Instead of greeting Michael with care and love—as Tom Hagen does when he first sees Michael, and as an older brother should do after not having seen his younger brother in quite some time—Fredo flicks the back of Michael’s head. While this gesture suggests a kind of playful intimacy, it underscores Fredo’s immaturity and inability to socialize with people in a more dignified way. The blocking of the action in the scene—with Fredo kneeling between Michael and Kay—also conveys his awkwardness and divisiveness. Michael’s act of bringing Kay to the wedding shows his devotion to her and telegraphs that one day, they too might get married. When Fredo sits between them, he separates the two and effectively disrupts the natural state of the couple. Though Sonny Corleone, the oldest son and therefore the eventual successor to the family business, shares few of Fredo’s character traits, he is also unlike his father in both personality and values. His reckless and impulsive nature is dramatized in his interaction with the FBI agents who are documenting, in an act of surveillance, the people who are attending the wedding. After unsuccessfully attempting to get the agents to leave and being met instead with a stoic face and an FBI ID, Sonny takes his frustration out on one of the agents, yanking his camera away and throwing it on the ground. Afterwards, he’s held back by Peter Clemenza; if Clemenza had not been there, Sonny would have likely thrown some punches. Then, in classic gangster fashion, he drops a couple of crumpled bills on the ground to pay for the broken camera.

Though Sonny Corleone, the oldest son and therefore the eventual successor to the family business, shares few of Fredo’s character traits, he is also unlike his father in both personality and values. His reckless and impulsive nature is dramatized in his interaction with the FBI agents who are documenting, in an act of surveillance, the people who are attending the wedding. After unsuccessfully attempting to get the agents to leave and being met instead with a stoic face and an FBI ID, Sonny takes his frustration out on one of the agents, yanking his camera away and throwing it on the ground. Afterwards, he’s held back by Peter Clemenza; if Clemenza had not been there, Sonny would have likely thrown some punches. Then, in classic gangster fashion, he drops a couple of crumpled bills on the ground to pay for the broken camera. This moment from the wedding scene encapsulates well the cruelty of the irony. His wife is in the foreground, busy talking to other guests and joking about the size of his phallus—which in its own way is a form of endearment. Meanwhile Sonny is almost directly behind her, just having whispered into the bridesmaid’s ear to meet him in a more private setting. He is cheating on his wife literally behind her back, and her close proximity to him while he commits this act suggests how normal this sort of betrayal has become for him. He puts a little care into hiding his unfaithfulness, but his suspicious activities are not unnoticed by his wife, who looks behind her to find him, only to see that he is already gone.

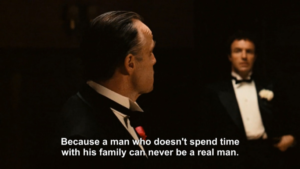

This moment from the wedding scene encapsulates well the cruelty of the irony. His wife is in the foreground, busy talking to other guests and joking about the size of his phallus—which in its own way is a form of endearment. Meanwhile Sonny is almost directly behind her, just having whispered into the bridesmaid’s ear to meet him in a more private setting. He is cheating on his wife literally behind her back, and her close proximity to him while he commits this act suggests how normal this sort of betrayal has become for him. He puts a little care into hiding his unfaithfulness, but his suspicious activities are not unnoticed by his wife, who looks behind her to find him, only to see that he is already gone. While talking to Johnny Fontane, he asks him if he spends time with his family, which Johnny replies affirmatively to. He follows up with a bit of moral instruction—“Because a man who doesn’t spend time with his family can never be a real man”—and here he looks directly at Sonny, directing the line more to him than to Johnny. Vito doesn’t address the issue in a private one-on-one, but he doesn’t need to, as this line serves as his condemnation of Sonny’s act. And in this condemnation, he embarrasses his son for failing to be a “real man” and a proper Corleone father.

While talking to Johnny Fontane, he asks him if he spends time with his family, which Johnny replies affirmatively to. He follows up with a bit of moral instruction—“Because a man who doesn’t spend time with his family can never be a real man”—and here he looks directly at Sonny, directing the line more to him than to Johnny. Vito doesn’t address the issue in a private one-on-one, but he doesn’t need to, as this line serves as his condemnation of Sonny’s act. And in this condemnation, he embarrasses his son for failing to be a “real man” and a proper Corleone father. While Michael may not be as immature as his two older brothers, the moment he walks into the wedding a distinction is already made between him and the rest of his family. As he walks into the estate with Kay, noticeably late—13 minutes already into the film to be exact—his military uniform sticks out like a sore thumb. Michael makes deliberate choices to differentiate himself from the rest of the Corleone family, showing up when he wants to instead of at the beginning of the wedding, wearing what he wants to instead of a tuxedo like the rest of his brothers, and bringing a non-Italian-American date (who herself chooses to wear a dress that is Americana in style). These choices construct his character as just another attendee and not a central member of the Corleone family. In his first interaction with a member of the family, Michael hears from Tom that his father is looking for him.

While Michael may not be as immature as his two older brothers, the moment he walks into the wedding a distinction is already made between him and the rest of his family. As he walks into the estate with Kay, noticeably late—13 minutes already into the film to be exact—his military uniform sticks out like a sore thumb. Michael makes deliberate choices to differentiate himself from the rest of the Corleone family, showing up when he wants to instead of at the beginning of the wedding, wearing what he wants to instead of a tuxedo like the rest of his brothers, and bringing a non-Italian-American date (who herself chooses to wear a dress that is Americana in style). These choices construct his character as just another attendee and not a central member of the Corleone family. In his first interaction with a member of the family, Michael hears from Tom that his father is looking for him. Coppola cuts to a close-up shot here, placing emphasis on both the importance of the statement as well as the secrecy of it—as it is family business—to ensure that Kay will not overhear. But Michael barely reciprocates, simply nodding before sitting back down to continue dining with Kay. This is a direct rejection of Vito, and more generally a rejection of any effort to craft stronger ties with his family and the dubious business they deal in.

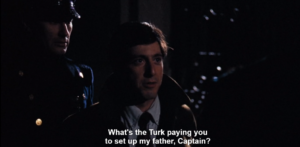

Coppola cuts to a close-up shot here, placing emphasis on both the importance of the statement as well as the secrecy of it—as it is family business—to ensure that Kay will not overhear. But Michael barely reciprocates, simply nodding before sitting back down to continue dining with Kay. This is a direct rejection of Vito, and more generally a rejection of any effort to craft stronger ties with his family and the dubious business they deal in. Michael’s decision to create a strong distinction between himself and his family is epitomized in a later scene in which he recounts the story of how Vito helped launch Johnny’s solo career. As he relates Vito’s criminal activities to Kay in vivid detail, he ends with the line “That’s my family Kay. It’s not me.” Michael makes it clear to Kay that he no longer feels a sense of belonging within his own family. It appears that Michael, decked out in his military uniform, is attempting to rebrand himself as a law-abiding, patriotic citizen — the exact opposite of a Corleone.

Michael’s decision to create a strong distinction between himself and his family is epitomized in a later scene in which he recounts the story of how Vito helped launch Johnny’s solo career. As he relates Vito’s criminal activities to Kay in vivid detail, he ends with the line “That’s my family Kay. It’s not me.” Michael makes it clear to Kay that he no longer feels a sense of belonging within his own family. It appears that Michael, decked out in his military uniform, is attempting to rebrand himself as a law-abiding, patriotic citizen — the exact opposite of a Corleone. Furthermore, we can see that, outside of his decisions to distance himself from the family, Michael is still a bearer of Sicilian values and culture: he talks about Sicilian family titles, recounts stories regarding his father, and even waltzes with his significant other, much like Vito is seen doing at various points in the wedding.

Furthermore, we can see that, outside of his decisions to distance himself from the family, Michael is still a bearer of Sicilian values and culture: he talks about Sicilian family titles, recounts stories regarding his father, and even waltzes with his significant other, much like Vito is seen doing at various points in the wedding.