Mixing Business with Pleasure: Alcohol in The Godfather

By Neha Zahid

Alcoholic beverages – wines and spirits – are an essential aspect of Italian-American dining culture. A meal without a drink is no meal at all. Similarly, a scene without a drink is incomplete.

In Coppola’s The Godfather – a film that follows the Corleones as they try to balance their dangerous business with their personal matters – there are sixty-one scenes that feature characters drinking. There are three dominant drinks in the film—scotch, red wine, and white wine—and each type of drink correlates to a distinct role in the film. Scotch is a “man’s drink”; red wine a family drink; and white wine a party drink.

There are three main drinks in the film: scotch, a “man’s drink”; red wine, a family drink; and white wine, a party drink. But the drinks start to blur as the line between what “business” and what’s “personal” begins to blur as well.

These associations are developed across the film but are especially highlighted in three scenes – the opening scene, Connie’s wedding scene, and the Las Vegas scene. Yet although these different drinks begin with distinct associations in the film, the drinks themselves start to blur as the title of “godfather” passes from Vito to Michael, and as the line between what’s “business” and what’s “personal” begins to blur as well.

***

The films open with a conversation between Bonasera and Vito (the godfather), in which Bonasera pleads for the godfather’s help to seek avenge his daughter’s assaulters. Bonasera is explaining the details of the account and begins to tear up. He apologizes for this unmasculine moment and then Vito prompts his men to give Bonasera a drink — a glass of scotch.

The first drink of the film is a hard, dark spirit. The lens focuses on Bonasera’s eyes and with his voice trembling, body shaking in shock and fear of the horrific events his daughter endured, he sips on the drink and settles it on his lap. The camera zooms out, his eyes no longer in focus, and his voice returns to normal. As Bonasera regains his composure, it becomes clear that the drink functions to give him courage – and, in effect, to regain his masculinity. But Vito’s scotch not only transfers power to his guest; it also asserts Vito’s superiority and power.

Scotch, throughout the film, is present during meetings between men; it is not observed in any scene involving women. It is presented as a peace offering during meetings, a welcoming gesture for males, and as a mode of relaxation for men. No matter the scene in which it appears, scotch symbolizes a significant power dynamic between the men who offer it and the men who drink it.

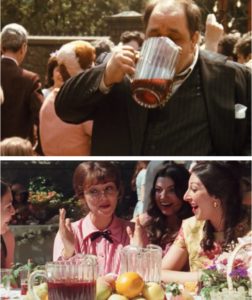

Directly after this encounter between Bonasera and Vito is Connie’s wedding scene. The choice of drink? Wine. Red wine. Red wine is an Italian necessity. It complements the lavish gathering and joyful energy. The film, in a future scene, alludes to the health benefits of red wine. Vito explains to Michael that he has been drinking more red wine in his old age to which Michael responds with, “It’s good for you.”

The association between red wine and good health is developed throughout Connie’s wedding. Men are seen drinking red wine while dancing to upbeat music. Clemenza drinks red wine as a replacement for water after exhausting himself in a dance. Pitchers of wine rest on tables — as essential as the centerpieces. Women are seen sipping red wine during casual conversations. Michael and Kay drink red wine along with their meals during a private conversation in which Michael is explaining the roles of members of the Corleone family. Young women enjoy red wine while gossiping about men. Every guest, old or young, male or female, is seen with a glass of red wine in hand. Red wine, then, has a strong connection with not only Italian culture, but also family.

It serves to bring people together, regardless of the “business behind the scenes.” In the wedding scene, the viewers are repeatedly taken from the cheerful events of the wedding to the serious discussions in the Don’s private office. Despite these ominous transitions, we are constantly comforted by the presence of red wine.

***

White wine is starkly different than the former two types of drinks. There is just one scene that involves white wine – the scene in Las Vegas where Michael proposes to buy out Moe Greene. Here the only people drinking white wine are the women whom Fredo hires for Michael (Johnny Fontane is holding a glass of white wine but never actually takes a sip). Within this context, white wine serves more as a party drink. Its lightness, in both color and strength of alcohol, represents the environment it tries to create – light, fun, worry-free. And indeed, it is a fun environment: music is playing, the girls are smiling, the colors are vibrant.

However, Michael immediately prompts Fredo to get rid of the “party” elements – the women and the band – because he is “here on business.” Strictly business.

The drink of choice, we might infer, should have been scotch. Fredo insults Michael’s masculinity by presuming the fun environment as appropriate for his interaction with his brother. Fredo further insults Michael by disrespecting and questioning his decisions in front of non-family members.

Clearly there is a disconnect between Fredo’s and Michael’s understanding of masculinity. Fredo’s perceived role in the Corleone family as an outcast relates to his misinterpretation of masculinity, family, and business. Fredo understands masculinity to be fun – in which white wine, a seemingly more feminine drink, is the drink of choice – and does not understand the seriousness of the Corleone business. It is this misunderstanding that results in his disrespecting of Michael. Where Michael was expecting scotch, Fredo was providing white wine.

***

Across the film, there is no clear progression of drinks: the type of drink is dependent on the scene and the environment. Sequential scenes tend to have a mix of drinks, primarily scotch and red wine, and the overlap further blurs the lines between business and personal.

Arguably the most prominent scene to highlight this blurred mixing of business and pleasure is the final scene. In Michael’s office, Kay is told by her sister-in-law Connie that Michael is responsible for the assassinations—including the murder of Connie’s husband Carlo—that have just occurred. In shock, Kay asks Michael if it truly was his doing. He says no — a lie.

Kay, in relief, hugs Michael and calls for a drink. But what drink will it be? The camera is angled on Kay pouring two glasses; the figure of Michael is in the background. We as viewers cannot see which drink she is deciding to pour.

Kay hugs Michael and calls for a drink—but what drink will it be? The audience, much like Kay, is left in the dark.

If Kay truly believed Michael, red wine would be the appropriate drink, as it represents celebration of the bonds of family. But then we see, from Kay’s perspective, Michael’s men approach him and shake his hands, honoring him as the new Don Corleone.

The office door closes and Kay is shut out from the truth — and the look on her face does not suggest that this is a happy outcome; she has poured two glasses, but the shut door keeps the two of them from sharing drinks and sharing a moment. Perhaps the drinks should be scotch, to signify Michael’s masculinity, his power, and his capacity for deceit — a capacity that Kay may now recognize.

Ultimately, the audience, much like Kay, is left in the dark. The drink is unknown; the future of Michael and Kay, uncertain.

Early in the opening wedding scene of The Godfather, a photographer lines up the Corleone family, preparing a family photo to solemnize the marriage of Constanzia, or Connie, Corleone to Carlo Rizzi. Yet Vito Corleone, the Don of this Sicilian family, notes his youngest son’s absence and so stops the shot from being taken: “We’re not taking the picture without Michael.” A picture is forever, and Vito—the center of the family, and with an especially soft spot for his son Michael—insists that all must be present and all must be willing to play their part. What Vito has created through the Corleone family is represented in its purest and most picturesque form by Connie’s wedding, which is huge, vibrant, and cheerful.

Early in the opening wedding scene of The Godfather, a photographer lines up the Corleone family, preparing a family photo to solemnize the marriage of Constanzia, or Connie, Corleone to Carlo Rizzi. Yet Vito Corleone, the Don of this Sicilian family, notes his youngest son’s absence and so stops the shot from being taken: “We’re not taking the picture without Michael.” A picture is forever, and Vito—the center of the family, and with an especially soft spot for his son Michael—insists that all must be present and all must be willing to play their part. What Vito has created through the Corleone family is represented in its purest and most picturesque form by Connie’s wedding, which is huge, vibrant, and cheerful. In the first shot following Vito’s dealings with Amerigo Bonasera, we glimpse the throng that has assembled for the event: though a tree covers half of the crowd, there are still dozens of visible people milling around, and by placing the camera far from the event, the individual people become a blur and turn into one huge sea of costumed bodies. The image suggests how, to the Corleones, a family should function: though the individuals that make up the larger family business are essential to its workings, they are all under the guise of one group and so are united by that group. Even with a sizable attendance already inside the estate, people can be seen still walking into the courtyard. Everyone, from tiny toddlers to their aging grandparents, must come and pay respects to Connie in this momentous event.

In the first shot following Vito’s dealings with Amerigo Bonasera, we glimpse the throng that has assembled for the event: though a tree covers half of the crowd, there are still dozens of visible people milling around, and by placing the camera far from the event, the individual people become a blur and turn into one huge sea of costumed bodies. The image suggests how, to the Corleones, a family should function: though the individuals that make up the larger family business are essential to its workings, they are all under the guise of one group and so are united by that group. Even with a sizable attendance already inside the estate, people can be seen still walking into the courtyard. Everyone, from tiny toddlers to their aging grandparents, must come and pay respects to Connie in this momentous event. Yet Vito is not just a man who spends a lot of money to make his daughter’s wedding a great celebration; he’s the sort of father who actively shows his care with that money by partaking in the festivities, spending time with his family throughout despite his ongoing business deals behind the scenes. This scene fills the wedding with his attention and care as he dances with his wife in the midst of the crowd. Smiles on their faces, the couple waltz as Vito makes an inaudible comment to his wife that conveys the couple’s agreeable intimacy.

Yet Vito is not just a man who spends a lot of money to make his daughter’s wedding a great celebration; he’s the sort of father who actively shows his care with that money by partaking in the festivities, spending time with his family throughout despite his ongoing business deals behind the scenes. This scene fills the wedding with his attention and care as he dances with his wife in the midst of the crowd. Smiles on their faces, the couple waltz as Vito makes an inaudible comment to his wife that conveys the couple’s agreeable intimacy. This scene is mirrored again at the end of the wedding: Vito leads his daughter through the crowd of clapping attendees, clutching her hand tightly. Holding hands is a sign of affection often seen between a parent and a young child, and in this context the meaning is still valid—perhaps even more so due to Connie’s older age and the likelihood that they no longer are so physically close. As Vito carefully lays his hand on her waist and they begin to waltz, Connie speaks inaudibly to him, causing them both to smile. When the scene cuts to a shot farther away from the two, Connie hugs him tightly as they continue their waltz. This increased physical affection suggests their own emotional intimacy, which they unabashedly display on stage.

This scene is mirrored again at the end of the wedding: Vito leads his daughter through the crowd of clapping attendees, clutching her hand tightly. Holding hands is a sign of affection often seen between a parent and a young child, and in this context the meaning is still valid—perhaps even more so due to Connie’s older age and the likelihood that they no longer are so physically close. As Vito carefully lays his hand on her waist and they begin to waltz, Connie speaks inaudibly to him, causing them both to smile. When the scene cuts to a shot farther away from the two, Connie hugs him tightly as they continue their waltz. This increased physical affection suggests their own emotional intimacy, which they unabashedly display on stage. Instead of greeting Michael with care and love—as Tom Hagen does when he first sees Michael, and as an older brother should do after not having seen his younger brother in quite some time—Fredo flicks the back of Michael’s head. While this gesture suggests a kind of playful intimacy, it underscores Fredo’s immaturity and inability to socialize with people in a more dignified way. The blocking of the action in the scene—with Fredo kneeling between Michael and Kay—also conveys his awkwardness and divisiveness. Michael’s act of bringing Kay to the wedding shows his devotion to her and telegraphs that one day, they too might get married. When Fredo sits between them, he separates the two and effectively disrupts the natural state of the couple.

Instead of greeting Michael with care and love—as Tom Hagen does when he first sees Michael, and as an older brother should do after not having seen his younger brother in quite some time—Fredo flicks the back of Michael’s head. While this gesture suggests a kind of playful intimacy, it underscores Fredo’s immaturity and inability to socialize with people in a more dignified way. The blocking of the action in the scene—with Fredo kneeling between Michael and Kay—also conveys his awkwardness and divisiveness. Michael’s act of bringing Kay to the wedding shows his devotion to her and telegraphs that one day, they too might get married. When Fredo sits between them, he separates the two and effectively disrupts the natural state of the couple. Though Sonny Corleone, the oldest son and therefore the eventual successor to the family business, shares few of Fredo’s character traits, he is also unlike his father in both personality and values. His reckless and impulsive nature is dramatized in his interaction with the FBI agents who are documenting, in an act of surveillance, the people who are attending the wedding. After unsuccessfully attempting to get the agents to leave and being met instead with a stoic face and an FBI ID, Sonny takes his frustration out on one of the agents, yanking his camera away and throwing it on the ground. Afterwards, he’s held back by Peter Clemenza; if Clemenza had not been there, Sonny would have likely thrown some punches. Then, in classic gangster fashion, he drops a couple of crumpled bills on the ground to pay for the broken camera.

Though Sonny Corleone, the oldest son and therefore the eventual successor to the family business, shares few of Fredo’s character traits, he is also unlike his father in both personality and values. His reckless and impulsive nature is dramatized in his interaction with the FBI agents who are documenting, in an act of surveillance, the people who are attending the wedding. After unsuccessfully attempting to get the agents to leave and being met instead with a stoic face and an FBI ID, Sonny takes his frustration out on one of the agents, yanking his camera away and throwing it on the ground. Afterwards, he’s held back by Peter Clemenza; if Clemenza had not been there, Sonny would have likely thrown some punches. Then, in classic gangster fashion, he drops a couple of crumpled bills on the ground to pay for the broken camera. This moment from the wedding scene encapsulates well the cruelty of the irony. His wife is in the foreground, busy talking to other guests and joking about the size of his phallus—which in its own way is a form of endearment. Meanwhile Sonny is almost directly behind her, just having whispered into the bridesmaid’s ear to meet him in a more private setting. He is cheating on his wife literally behind her back, and her close proximity to him while he commits this act suggests how normal this sort of betrayal has become for him. He puts a little care into hiding his unfaithfulness, but his suspicious activities are not unnoticed by his wife, who looks behind her to find him, only to see that he is already gone.

This moment from the wedding scene encapsulates well the cruelty of the irony. His wife is in the foreground, busy talking to other guests and joking about the size of his phallus—which in its own way is a form of endearment. Meanwhile Sonny is almost directly behind her, just having whispered into the bridesmaid’s ear to meet him in a more private setting. He is cheating on his wife literally behind her back, and her close proximity to him while he commits this act suggests how normal this sort of betrayal has become for him. He puts a little care into hiding his unfaithfulness, but his suspicious activities are not unnoticed by his wife, who looks behind her to find him, only to see that he is already gone. While talking to Johnny Fontane, he asks him if he spends time with his family, which Johnny replies affirmatively to. He follows up with a bit of moral instruction—“Because a man who doesn’t spend time with his family can never be a real man”—and here he looks directly at Sonny, directing the line more to him than to Johnny. Vito doesn’t address the issue in a private one-on-one, but he doesn’t need to, as this line serves as his condemnation of Sonny’s act. And in this condemnation, he embarrasses his son for failing to be a “real man” and a proper Corleone father.

While talking to Johnny Fontane, he asks him if he spends time with his family, which Johnny replies affirmatively to. He follows up with a bit of moral instruction—“Because a man who doesn’t spend time with his family can never be a real man”—and here he looks directly at Sonny, directing the line more to him than to Johnny. Vito doesn’t address the issue in a private one-on-one, but he doesn’t need to, as this line serves as his condemnation of Sonny’s act. And in this condemnation, he embarrasses his son for failing to be a “real man” and a proper Corleone father. While Michael may not be as immature as his two older brothers, the moment he walks into the wedding a distinction is already made between him and the rest of his family. As he walks into the estate with Kay, noticeably late—13 minutes already into the film to be exact—his military uniform sticks out like a sore thumb. Michael makes deliberate choices to differentiate himself from the rest of the Corleone family, showing up when he wants to instead of at the beginning of the wedding, wearing what he wants to instead of a tuxedo like the rest of his brothers, and bringing a non-Italian-American date (who herself chooses to wear a dress that is Americana in style). These choices construct his character as just another attendee and not a central member of the Corleone family. In his first interaction with a member of the family, Michael hears from Tom that his father is looking for him.

While Michael may not be as immature as his two older brothers, the moment he walks into the wedding a distinction is already made between him and the rest of his family. As he walks into the estate with Kay, noticeably late—13 minutes already into the film to be exact—his military uniform sticks out like a sore thumb. Michael makes deliberate choices to differentiate himself from the rest of the Corleone family, showing up when he wants to instead of at the beginning of the wedding, wearing what he wants to instead of a tuxedo like the rest of his brothers, and bringing a non-Italian-American date (who herself chooses to wear a dress that is Americana in style). These choices construct his character as just another attendee and not a central member of the Corleone family. In his first interaction with a member of the family, Michael hears from Tom that his father is looking for him. Coppola cuts to a close-up shot here, placing emphasis on both the importance of the statement as well as the secrecy of it—as it is family business—to ensure that Kay will not overhear. But Michael barely reciprocates, simply nodding before sitting back down to continue dining with Kay. This is a direct rejection of Vito, and more generally a rejection of any effort to craft stronger ties with his family and the dubious business they deal in.

Coppola cuts to a close-up shot here, placing emphasis on both the importance of the statement as well as the secrecy of it—as it is family business—to ensure that Kay will not overhear. But Michael barely reciprocates, simply nodding before sitting back down to continue dining with Kay. This is a direct rejection of Vito, and more generally a rejection of any effort to craft stronger ties with his family and the dubious business they deal in. Michael’s decision to create a strong distinction between himself and his family is epitomized in a later scene in which he recounts the story of how Vito helped launch Johnny’s solo career. As he relates Vito’s criminal activities to Kay in vivid detail, he ends with the line “That’s my family Kay. It’s not me.” Michael makes it clear to Kay that he no longer feels a sense of belonging within his own family. It appears that Michael, decked out in his military uniform, is attempting to rebrand himself as a law-abiding, patriotic citizen — the exact opposite of a Corleone.

Michael’s decision to create a strong distinction between himself and his family is epitomized in a later scene in which he recounts the story of how Vito helped launch Johnny’s solo career. As he relates Vito’s criminal activities to Kay in vivid detail, he ends with the line “That’s my family Kay. It’s not me.” Michael makes it clear to Kay that he no longer feels a sense of belonging within his own family. It appears that Michael, decked out in his military uniform, is attempting to rebrand himself as a law-abiding, patriotic citizen — the exact opposite of a Corleone. Furthermore, we can see that, outside of his decisions to distance himself from the family, Michael is still a bearer of Sicilian values and culture: he talks about Sicilian family titles, recounts stories regarding his father, and even waltzes with his significant other, much like Vito is seen doing at various points in the wedding.

Furthermore, we can see that, outside of his decisions to distance himself from the family, Michael is still a bearer of Sicilian values and culture: he talks about Sicilian family titles, recounts stories regarding his father, and even waltzes with his significant other, much like Vito is seen doing at various points in the wedding.

As the head of the Family, Vito is not stripped of his patriarchal position when he sits down. Rather, his status is elevated: he is a king upon his throne. With all eyes drawn toward him, he is careful to use limited and deliberate physical gestures to conceal his thoughts and emotions. When Tom Hagen briefs Vito about Sollozzo’s request to receive protection in exchange for a percentage of the profits of his drug trade, Vito sits with his legs crossed while reclining in his seat. Before the meeting with Sollozzo commences, Vito nods his head, shrugs his shoulders, and sways—as if he were doing Sollozzo a favor by indulging his offer, only bestowing the minimum physical attention required to hear his request. He also asks Tom if he is “not too tired,” as if to suggest his own fatigue as the Don. His body language reveals a disinclination towards stretching the reach of the Family business, as it jeopardizes the familial affiliations that he has established within and outside his blood ties. When Sonny asks him what his decision is going to be, Vito raises his hand from his cheek before resting it on his chin, withholding his thoughts until the next scene.

As the head of the Family, Vito is not stripped of his patriarchal position when he sits down. Rather, his status is elevated: he is a king upon his throne. With all eyes drawn toward him, he is careful to use limited and deliberate physical gestures to conceal his thoughts and emotions. When Tom Hagen briefs Vito about Sollozzo’s request to receive protection in exchange for a percentage of the profits of his drug trade, Vito sits with his legs crossed while reclining in his seat. Before the meeting with Sollozzo commences, Vito nods his head, shrugs his shoulders, and sways—as if he were doing Sollozzo a favor by indulging his offer, only bestowing the minimum physical attention required to hear his request. He also asks Tom if he is “not too tired,” as if to suggest his own fatigue as the Don. His body language reveals a disinclination towards stretching the reach of the Family business, as it jeopardizes the familial affiliations that he has established within and outside his blood ties. When Sonny asks him what his decision is going to be, Vito raises his hand from his cheek before resting it on his chin, withholding his thoughts until the next scene. After he inherits Vito’s throne, Michael’s sitting posture recalls his father’s — but with some striking differences. When Michael offers a plan to exact retribution for his father’s shooting, he positions himself in an armchair in a similar manner to his father, crossing his legs and lolling in the furniture. However, Michael is not as calm and collected as Vito had been: he rubs his eyebrows and slumps in his chair, moving his body back and forth before proceeding with his plan. He’s restless—sweaty and squirming. He wants to take immediate action, but he does not act upon his impulses. In the following moments, he places both arms on the handles of the chair as a way to ground himself within the turbulence. As the camera zooms in, Michael’s body becomes more relaxed while still tilting forward: we sense that he is more comfortable with his position, prepared to prove his power. He slurs his words, recalling how his father often mumbles his words, but he does so in anger, his gestures intensified by the sternness of his stare and speech.

After he inherits Vito’s throne, Michael’s sitting posture recalls his father’s — but with some striking differences. When Michael offers a plan to exact retribution for his father’s shooting, he positions himself in an armchair in a similar manner to his father, crossing his legs and lolling in the furniture. However, Michael is not as calm and collected as Vito had been: he rubs his eyebrows and slumps in his chair, moving his body back and forth before proceeding with his plan. He’s restless—sweaty and squirming. He wants to take immediate action, but he does not act upon his impulses. In the following moments, he places both arms on the handles of the chair as a way to ground himself within the turbulence. As the camera zooms in, Michael’s body becomes more relaxed while still tilting forward: we sense that he is more comfortable with his position, prepared to prove his power. He slurs his words, recalling how his father often mumbles his words, but he does so in anger, his gestures intensified by the sternness of his stare and speech. Vito and Michael both use hand movements that reveal them suppressing their anger and frustration. In the opening scene, mortician Amerigo Bonasera offers to pay Vito Corleone in exchange for revenge upon the men who abused his daughter—an offer which offends the Don, as it insinuates he is both a killer and can be “bought.” Prior to this exact moment, Vito’s hand is petting and playing with a cat sitting on his lap; just after, his grip tightens around the animal’s head. The sequence of gestures suggests a few meanings: (1) he is crushing his urge to act upon his anger towards Amerigo Bonasera—he is a man, “not a murderer”—which would demonstrate a childish weakness that cannot be associated with the patriarch of a family, let alone the Family; and (2) given that the image of a cat often carries both feminine and sexual connotations, Vito’s intensifying hold shows him flexing his masculine power and exerting his dominance, his full control.

Vito and Michael both use hand movements that reveal them suppressing their anger and frustration. In the opening scene, mortician Amerigo Bonasera offers to pay Vito Corleone in exchange for revenge upon the men who abused his daughter—an offer which offends the Don, as it insinuates he is both a killer and can be “bought.” Prior to this exact moment, Vito’s hand is petting and playing with a cat sitting on his lap; just after, his grip tightens around the animal’s head. The sequence of gestures suggests a few meanings: (1) he is crushing his urge to act upon his anger towards Amerigo Bonasera—he is a man, “not a murderer”—which would demonstrate a childish weakness that cannot be associated with the patriarch of a family, let alone the Family; and (2) given that the image of a cat often carries both feminine and sexual connotations, Vito’s intensifying hold shows him flexing his masculine power and exerting his dominance, his full control. Michael, on the other hand, is less composed and constrained in his physical mannerisms—his body is seemingly riddled with anxiety. After Michael’s return from Sicily, he makes significant decisions as the new “head of the Family,” including relocating the business transactions to Las Vegas and replacing Tom Hagen as consigliere. During this scene, Michael is twiddling a zippo lighter between his fingers, smoking a cigarette, and prolongedly pressing it into an ashtray.

Michael, on the other hand, is less composed and constrained in his physical mannerisms—his body is seemingly riddled with anxiety. After Michael’s return from Sicily, he makes significant decisions as the new “head of the Family,” including relocating the business transactions to Las Vegas and replacing Tom Hagen as consigliere. During this scene, Michael is twiddling a zippo lighter between his fingers, smoking a cigarette, and prolongedly pressing it into an ashtray.

After the opening scene, Don Vito runs a hand against his grey, slicked-backed hair and qualifies his terms for the mortician’s debt: “We’re not murderers, despite what this undertaker says.” In this scene, Vito is literally scratching his head at his decision to expand the scope of the Family to meet the pleas of an acquaintance who has deliberately avoided them. Yet Vito’s grooming habit is second nature to him—he stays in character as the cool and collected Don.

After the opening scene, Don Vito runs a hand against his grey, slicked-backed hair and qualifies his terms for the mortician’s debt: “We’re not murderers, despite what this undertaker says.” In this scene, Vito is literally scratching his head at his decision to expand the scope of the Family to meet the pleas of an acquaintance who has deliberately avoided them. Yet Vito’s grooming habit is second nature to him—he stays in character as the cool and collected Don. This gesture is replayed in a different key in the pivotal scene at the Italian restaurant, in which Michael struggles to carry out the plot he proposed—to kill Sollozzo and his police guard. Just after he retrieves the gun from the restaurant’s toilet, Michael stands in front of the bathroom’s mirror and presses both hands against his hair in an attempt to gather himself. Here, Michael is on the edge of becoming a part of the family — a family that he had pointedly described, to his girlfriend Kay, as “not me”. His fingers are pushed against his head—he is trying to wrap his brain around his decision. By executing his plan, he not only will be initiated into the business, but also will finally be able to feel like a part of the Corleone family by embodying the role of his father. With the gun concealed in his jacket, Michael seats himself at the table with Sollozzo and his police guard; he brushes his hair back and switches from speaking in Italian to English when staking his claim: “What’s most important to me is that I have a guarantee: no more attempts on my father’s life.” By protecting the patriarch, Michael secures his succession.

This gesture is replayed in a different key in the pivotal scene at the Italian restaurant, in which Michael struggles to carry out the plot he proposed—to kill Sollozzo and his police guard. Just after he retrieves the gun from the restaurant’s toilet, Michael stands in front of the bathroom’s mirror and presses both hands against his hair in an attempt to gather himself. Here, Michael is on the edge of becoming a part of the family — a family that he had pointedly described, to his girlfriend Kay, as “not me”. His fingers are pushed against his head—he is trying to wrap his brain around his decision. By executing his plan, he not only will be initiated into the business, but also will finally be able to feel like a part of the Corleone family by embodying the role of his father. With the gun concealed in his jacket, Michael seats himself at the table with Sollozzo and his police guard; he brushes his hair back and switches from speaking in Italian to English when staking his claim: “What’s most important to me is that I have a guarantee: no more attempts on my father’s life.” By protecting the patriarch, Michael secures his succession. When Vito meets with Sollozzo to listen to his proposition (only to decline), his blazer is unbuttoned, and he droops one arm over the chair while the other dangles from his hip. Vito gives the appearance of approachability while still upholding his authority—he does not need to exercise his dominance in the situation because his mere presence is enough. Vito’s amiability is not so much a sign of respect for Sollozzo, but a means of maintaining respectability as a representative of the Corleone tribe. As Vito turns down Sollozzo’s request, his hands are clasped, but not fastened together, and he strokes and shrugs his thumbs: “It doesn’t make any difference to me what a man does for a living.” Vito is not interested in what can be done to advance his enterprise, but in what he can do to preserve the relationships with his current business partners.

When Vito meets with Sollozzo to listen to his proposition (only to decline), his blazer is unbuttoned, and he droops one arm over the chair while the other dangles from his hip. Vito gives the appearance of approachability while still upholding his authority—he does not need to exercise his dominance in the situation because his mere presence is enough. Vito’s amiability is not so much a sign of respect for Sollozzo, but a means of maintaining respectability as a representative of the Corleone tribe. As Vito turns down Sollozzo’s request, his hands are clasped, but not fastened together, and he strokes and shrugs his thumbs: “It doesn’t make any difference to me what a man does for a living.” Vito is not interested in what can be done to advance his enterprise, but in what he can do to preserve the relationships with his current business partners. Michael is not as gentle, however, when he arrives in Las Vegas to buy Moe Greene’s casino and offer Johnny Fontaine a new contract. In this scene, Michael clasps his hands as well, except with his thumbs pressed together. Not only is he steadfast in his position, but also he’s confident that no one in the room can “refuse” him nor the strength he flexes. Moe Greene then barges in and argues with Michael over the notion that he can “buy [him] out,” and Fredo defends Moe and questions Michael’s reasoning. Echoing the earlier scene in which his father advised Sonny to “never tell anyone outside the family what [he thinks] again,” Michael warns Fredo never to “take sides with anyone against the family again.”

Michael is not as gentle, however, when he arrives in Las Vegas to buy Moe Greene’s casino and offer Johnny Fontaine a new contract. In this scene, Michael clasps his hands as well, except with his thumbs pressed together. Not only is he steadfast in his position, but also he’s confident that no one in the room can “refuse” him nor the strength he flexes. Moe Greene then barges in and argues with Michael over the notion that he can “buy [him] out,” and Fredo defends Moe and questions Michael’s reasoning. Echoing the earlier scene in which his father advised Sonny to “never tell anyone outside the family what [he thinks] again,” Michael warns Fredo never to “take sides with anyone against the family again.”

In their final interaction in the film, Michael is already Don of the Family and Vito is “retired.” The viewer can sense a shift in Vito’s demeanor; he is smiling, joking, drinking wine, and sitting with his right leg folded above the other. He is not hunched over, as he had been in many previous scenes. The burden of the Family business has been removed from his shoulders, and he can take it easy, if only for an instant.

In their final interaction in the film, Michael is already Don of the Family and Vito is “retired.” The viewer can sense a shift in Vito’s demeanor; he is smiling, joking, drinking wine, and sitting with his right leg folded above the other. He is not hunched over, as he had been in many previous scenes. The burden of the Family business has been removed from his shoulders, and he can take it easy, if only for an instant. Tellingly, when Vito positions himself in his seat, he obscures the image of Michael. The camera work suggests how succession works in this family: the importance of the patriarch means that there’s no room for others, just the single male head. To be powerful, to be head of the family: this aspiration is tied to Michael becoming singular, with a way of moving his body that—however indebted to his father—is his and his alone.

Tellingly, when Vito positions himself in his seat, he obscures the image of Michael. The camera work suggests how succession works in this family: the importance of the patriarch means that there’s no room for others, just the single male head. To be powerful, to be head of the family: this aspiration is tied to Michael becoming singular, with a way of moving his body that—however indebted to his father—is his and his alone.