The Sound of Nostalgia: Nino Rota’s “Godfather Waltz”

By Rebekah Gonzalez

Nino Rota once said, about his work as a composer, “They reckon my music’s just a bit of nostalgia plus lots of good humor and optimism? Well, that’s exactly how I’d like to be remembered.”

It is ironic, then, that his best-known work is the score to The Godfather—a film that, on the surface, offers violence and loss rather than “good humor and optimism.” Yet Rota’s Godfather score draws out aspects of the film that lie beneath the surface— its dark humor and its nostalgia —and helps give the film’s nostalgia its emotional pull and complexity. As a period film, its story set in the mid-1940s, though filmed through the scope of a 1970s camera, The Godfather cannot help but become subject to the yearning for a time before. That general nostalgia is amplified through another more specific nostalgia found within the film—the nostalgia that gives a charge to Vito and Michael Corleone’s relationship. This type of nostalgia is concerned with the future, but a future that has been tenuously predetermined.

It’s as if “The Godfather Waltz” says, “I never wanted this for you, Michael,” before Vito Corleone himself can say it.

Rota, we’ll see, translates the nostalgia of the father-son relationship into the music of the Main Title or “The Godfather Waltz.” Rota focuses on the dualities of the relationship. While the song serves as a roadmap for Michael’s future, it simultaneously explores Vito’s struggle with granting the reins of his deadly business to his son. The film seems to be cognizant of what the future holds, but while Coppola makes the audience, as well as the characters in the film, work towards this ending, Rota surreptitiously clues them in through his Main Title. It’s as if the “Godfather Waltz” says, “I never wanted this for you, Michael,” before Vito Corleone himself can say it.

***

(Nino Rota, “The Godfather Waltz,” from the soundtrack to The Godfather)

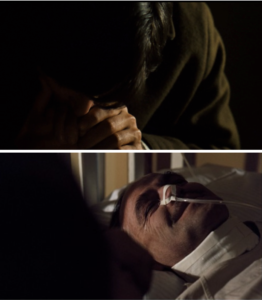

The film opens with a black screen, making the viewer’s first engagement with the film a purely auditory one. The trumpet plays the main melodic line of the waltz as the title of the movie appears and fades from the screen. After it plays through it once, Bonasera’s monologue begins. The only two characters on screen are Bonasera and Vito Corleone. It is clear that Vito is in a position of power. This is the first time the trumpet is attached to a scene with Vito. However, the connection is not made clear until the next time we hear the trumpet line at 46:05, when Vito is shot. As the dying Vito slides off his car and onto the ground, the melody is played at a higher key, making the powerful line of music sound frail.

At this point, it is clear that the trumpet is meant to represent Vito. It is never played when Vito is not somewhere in the shot. Directly after, the film dissolves into a shot of Radio City Music Hall, where Michael and Kay are leaving after watching a show. Although the trumpet fades away before Michael is on screen, this placement of the theme puts Michael in close proximity to his father’s haunting song. It also important to note that this is the last time we see Michael living a carefree and “normal” life; one not centered around the family business.

When Rota has the main melody played by oboe, not the trumpet we associate with Vito, he foreshadows how the role of Don will be passed onto Michael

The waltz is next used is at 58:08, and for the first time we hear past the trumpet solo. The trumpet solo is skipped and Rota instead uses an oboe to play the main melody. This choice solidifies the sense that the trumpet represents Vito, who has been sidelined by the hit on his life: the instrument that stood for him has gone quiet, and now other instruments must take up his theme. There is another dissolve into a shot of Michael; he is sitting outside looking down at his shoes. This time, instead of the trumpet solo fading out, the music continues into the traditional waltz portion of the piece: we sense, through the playing of theme, how the future of Vito’s business and legacy hangs over Michael’s head. During this particular moment of the waltz, the main melody has moved, once again, to the oboe. This orchestration foreshadows how the role of Don will be passed onto Michael, even though none of the characters expect it at this point in the film.

***

While Michael is hiding out in Sicily, the Waltz does not follow him there, which is surprising given its folkloric elements. At 1:20 on the soundtrack version of the “Godfather Waltz,” Rota has an accordion play a couple of bars of the main melody before switching back to the oboe. The use of the accordion can directly be associated with Italian folk music. This moment in the score foreshadows Michael’s stay in Sicily. It would seem logical, then, that this specific moment in the piece would be used in tandem with the scene that it is derived from. However, its absence speaks to the physical separation between Michael and Vito, and roots the Waltz to the specific nostalgia found in their father-son relationship. Vito is upset when he learns that Michael has committed murders in the name of the family business.

We might say that, just as the film uses its geographical locations to show that they are physically separated, Rota’s score— specifically the fact that the “Godfather Waltz” is not played—expresses that the two are also emotionally separated at this point in the film. More generally, we might observe that, despite being the main theme of the film, the “Godfather Waltz” is used strikingly sparely across the film. This scarce use of the theme aligns with the scarce number of scenes that Michael and Vito share alone. Because these scenes are rare, they also become packed with meaning and purpose.

It is also important to note that the waltz is never used during a scene in which Michael and Vito are alone. Rather, the waltz is placed in between scenes that transition from Vito to Michael. It is used to link their two characters as well as to dramatize the tension between the two of them while Michael is on his way to becoming the Don. The tension is not personal, but it does affect their relationship. There seems to be a barrier, which derives partly from Vito’s pride and partly from their lack of alone time, which keeps Vito from speaking directly with Michael.

Through the waltz, Rota is able to verbalize, through the melancholic minor mode of the theme’s melody, what Vito struggles to tell Michael. The Waltz formulates Vito’s emotions throughout the film until he can say them himself, in a scene that Coppola added during filming because he felt that the two of them—and the film itself—needed this moment of emotional connection. It is not until we are over two hours into the film that Vito tells Michael that he once pictured his son as “Senator Corleone, Governor Corleone,” and confesses that “I never wanted this for you.”

***

The “Godfather Waltz” is not heard again until the film’s closing scene. Although it is not technically considered the “Godfather Waltz,” the Finale draws upon the same waltz structure as well as the melody. The trumpet—lonely no more—blends with the rest of the orchestra as Michael’s hand is kissed and as he’s called, for the first time, “Don Corleone”; the swell of the music underlines that he has fully transitioned into his father’s position of power. The return of the trumpet also suggests that the trumpet was never associated with Vito himself, but rather with Vito as the Don. This, along with the cyclical structure of the waltz, alludes to the possibility that the family’s power might revive itself in this way again and again. Looking toward the past while announcing an eminent future, Rota’s “Godfather Waltz” establishes the particular nature of the Corleone family’s power: rooted in a never-ending nostalgia, and ever-seeking renewal.

Late in The Godfather, when Vito Corleone collapses to the ground and his grandson Anthony runs away to get help, viewers are left to look at the former Don’s body lying motionless in the shade of a trellised tomato garden. For five seconds, the only sounds that fill the soundtrack are the birds chirping and the wind blowing through the trees; then the image fades and funeral bells ring in the next scene. Unlike other critical scenes in the film, which rely on dramatic sequence and action, or intriguing dialogue between characters, this scene has a different way of registering with the viewer: its significance is encapsulated in the symbolic images that frame Vito’s final moments and the non-verbal gestures shared between Vito and his grandson.

Late in The Godfather, when Vito Corleone collapses to the ground and his grandson Anthony runs away to get help, viewers are left to look at the former Don’s body lying motionless in the shade of a trellised tomato garden. For five seconds, the only sounds that fill the soundtrack are the birds chirping and the wind blowing through the trees; then the image fades and funeral bells ring in the next scene. Unlike other critical scenes in the film, which rely on dramatic sequence and action, or intriguing dialogue between characters, this scene has a different way of registering with the viewer: its significance is encapsulated in the symbolic images that frame Vito’s final moments and the non-verbal gestures shared between Vito and his grandson. It is no accident that the central prop of this scene is a watering gun — an implement which evokes power and the potential for violence but does so lightly, even ironically. (Water, not bullets, issue from its ‘barrel’.) Just before this scene, Vito speaks to his son, Michael, in the same garden. In that scene, Vito grapples with the guilt and uncertainty of having to transfer his power down to the next generation. Handing his status and the family business to Michael, he wants also to advise his son and ensure that the business can flourish. Though Michael is not unkind with Vito, neither is he overly deferential: the scene signals clearly that Michael, as the new Don, will make his own decisions.

It is no accident that the central prop of this scene is a watering gun — an implement which evokes power and the potential for violence but does so lightly, even ironically. (Water, not bullets, issue from its ‘barrel’.) Just before this scene, Vito speaks to his son, Michael, in the same garden. In that scene, Vito grapples with the guilt and uncertainty of having to transfer his power down to the next generation. Handing his status and the family business to Michael, he wants also to advise his son and ensure that the business can flourish. Though Michael is not unkind with Vito, neither is he overly deferential: the scene signals clearly that Michael, as the new Don, will make his own decisions. Vito Corleone’s loss of power is reflected in his physical appearance and presentation. In the introductory scene of the film, Vito comes across as a powerful figure. His words carry weight and deliberation in his monologue; he wears a fine suit, and his hair neatly slicked back. By contrast, this scene presents Vito in casual clothing, and with unruly hair protruding out of his hat. His body appears languid and shriveled by age. It is a portrait of a powerless Don. Even the simple act of calling out to his grandson and extending his arm as gesture seems like an extra strain on his body.

Vito Corleone’s loss of power is reflected in his physical appearance and presentation. In the introductory scene of the film, Vito comes across as a powerful figure. His words carry weight and deliberation in his monologue; he wears a fine suit, and his hair neatly slicked back. By contrast, this scene presents Vito in casual clothing, and with unruly hair protruding out of his hat. His body appears languid and shriveled by age. It is a portrait of a powerless Don. Even the simple act of calling out to his grandson and extending his arm as gesture seems like an extra strain on his body. The only gesture of power that Vito conveys in this scene is reliant on artifice. To get his grandson’s attention, Vito cuts an orange peel and fashions a pair of fangs for his mouth. In his final exertion of power before he dies, he pretends to be a big and scary monster to frighten his grandson. The performance of power is what leads to his death — both literally, in this scene, and symbolically for the overall story arc of his character. Through much of the film, Vito has performed the role of mafia Don as the ultimate exertion of his power, but in this scene, viewers are offered a glimpse into what Vito Corleone looks like without his presentation and appearance as the powerful Don Corleone. When he adorns himself with a pair of fangs, to play pretend with his grandson, the scene frames the gesture as a representation of how Vito performs throughout the film; the only difference here is that viewers witness the process of how Vito transforms himself to convey power, even if it is just to frighten his grandson for a brief moment.

The only gesture of power that Vito conveys in this scene is reliant on artifice. To get his grandson’s attention, Vito cuts an orange peel and fashions a pair of fangs for his mouth. In his final exertion of power before he dies, he pretends to be a big and scary monster to frighten his grandson. The performance of power is what leads to his death — both literally, in this scene, and symbolically for the overall story arc of his character. Through much of the film, Vito has performed the role of mafia Don as the ultimate exertion of his power, but in this scene, viewers are offered a glimpse into what Vito Corleone looks like without his presentation and appearance as the powerful Don Corleone. When he adorns himself with a pair of fangs, to play pretend with his grandson, the scene frames the gesture as a representation of how Vito performs throughout the film; the only difference here is that viewers witness the process of how Vito transforms himself to convey power, even if it is just to frighten his grandson for a brief moment. Chasing his grandson through the tomato vines, Vito removes his orange peel fangs —and tellingly, it is at this moment that he erupts into the coughing fit that results in his collapse. Playing pretend with his grandson has been too much of a physical strain on his body; Vito gives up his monster act, and gives up the ghost. Likewise, Vito’s performance of power as Don has been the ultimate exertion in his life. He has structured his whole life and family around the power and persona of Don Corleone, and the toll ends up being too much to handle: Vito crumbles and falls in the tomato garden. He lies on the ground, next to the ripe, or possibly overripe, tomatoes that have burdened the vine branch with their own weight and have fallen to litter the soil.

Chasing his grandson through the tomato vines, Vito removes his orange peel fangs —and tellingly, it is at this moment that he erupts into the coughing fit that results in his collapse. Playing pretend with his grandson has been too much of a physical strain on his body; Vito gives up his monster act, and gives up the ghost. Likewise, Vito’s performance of power as Don has been the ultimate exertion in his life. He has structured his whole life and family around the power and persona of Don Corleone, and the toll ends up being too much to handle: Vito crumbles and falls in the tomato garden. He lies on the ground, next to the ripe, or possibly overripe, tomatoes that have burdened the vine branch with their own weight and have fallen to litter the soil. At the very moment of Vito’s death, Coppola notably cuts to a more distant shot. The camera frames the tomato garden at the center of the backyard; in the confines of the garden lies Vito’s body. The image of Vito resting on the soil, the foundation of the garden, resonates with Vito’s role as the foundation of his family and business. He has worked and exerted himself completely to maintain the growth of his personal and family legacy. As a result, like the ripe tomatoes that must fall to make room for new ones, Vito must fall in order to make room for the new Don, his son.

At the very moment of Vito’s death, Coppola notably cuts to a more distant shot. The camera frames the tomato garden at the center of the backyard; in the confines of the garden lies Vito’s body. The image of Vito resting on the soil, the foundation of the garden, resonates with Vito’s role as the foundation of his family and business. He has worked and exerted himself completely to maintain the growth of his personal and family legacy. As a result, like the ripe tomatoes that must fall to make room for new ones, Vito must fall in order to make room for the new Don, his son.

Early in the opening wedding scene of The Godfather, a photographer lines up the Corleone family, preparing a family photo to solemnize the marriage of Constanzia, or Connie, Corleone to Carlo Rizzi. Yet Vito Corleone, the Don of this Sicilian family, notes his youngest son’s absence and so stops the shot from being taken: “We’re not taking the picture without Michael.” A picture is forever, and Vito—the center of the family, and with an especially soft spot for his son Michael—insists that all must be present and all must be willing to play their part. What Vito has created through the Corleone family is represented in its purest and most picturesque form by Connie’s wedding, which is huge, vibrant, and cheerful.

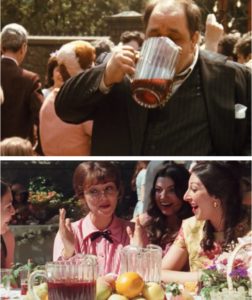

Early in the opening wedding scene of The Godfather, a photographer lines up the Corleone family, preparing a family photo to solemnize the marriage of Constanzia, or Connie, Corleone to Carlo Rizzi. Yet Vito Corleone, the Don of this Sicilian family, notes his youngest son’s absence and so stops the shot from being taken: “We’re not taking the picture without Michael.” A picture is forever, and Vito—the center of the family, and with an especially soft spot for his son Michael—insists that all must be present and all must be willing to play their part. What Vito has created through the Corleone family is represented in its purest and most picturesque form by Connie’s wedding, which is huge, vibrant, and cheerful. In the first shot following Vito’s dealings with Amerigo Bonasera, we glimpse the throng that has assembled for the event: though a tree covers half of the crowd, there are still dozens of visible people milling around, and by placing the camera far from the event, the individual people become a blur and turn into one huge sea of costumed bodies. The image suggests how, to the Corleones, a family should function: though the individuals that make up the larger family business are essential to its workings, they are all under the guise of one group and so are united by that group. Even with a sizable attendance already inside the estate, people can be seen still walking into the courtyard. Everyone, from tiny toddlers to their aging grandparents, must come and pay respects to Connie in this momentous event.

In the first shot following Vito’s dealings with Amerigo Bonasera, we glimpse the throng that has assembled for the event: though a tree covers half of the crowd, there are still dozens of visible people milling around, and by placing the camera far from the event, the individual people become a blur and turn into one huge sea of costumed bodies. The image suggests how, to the Corleones, a family should function: though the individuals that make up the larger family business are essential to its workings, they are all under the guise of one group and so are united by that group. Even with a sizable attendance already inside the estate, people can be seen still walking into the courtyard. Everyone, from tiny toddlers to their aging grandparents, must come and pay respects to Connie in this momentous event. Yet Vito is not just a man who spends a lot of money to make his daughter’s wedding a great celebration; he’s the sort of father who actively shows his care with that money by partaking in the festivities, spending time with his family throughout despite his ongoing business deals behind the scenes. This scene fills the wedding with his attention and care as he dances with his wife in the midst of the crowd. Smiles on their faces, the couple waltz as Vito makes an inaudible comment to his wife that conveys the couple’s agreeable intimacy.

Yet Vito is not just a man who spends a lot of money to make his daughter’s wedding a great celebration; he’s the sort of father who actively shows his care with that money by partaking in the festivities, spending time with his family throughout despite his ongoing business deals behind the scenes. This scene fills the wedding with his attention and care as he dances with his wife in the midst of the crowd. Smiles on their faces, the couple waltz as Vito makes an inaudible comment to his wife that conveys the couple’s agreeable intimacy. This scene is mirrored again at the end of the wedding: Vito leads his daughter through the crowd of clapping attendees, clutching her hand tightly. Holding hands is a sign of affection often seen between a parent and a young child, and in this context the meaning is still valid—perhaps even more so due to Connie’s older age and the likelihood that they no longer are so physically close. As Vito carefully lays his hand on her waist and they begin to waltz, Connie speaks inaudibly to him, causing them both to smile. When the scene cuts to a shot farther away from the two, Connie hugs him tightly as they continue their waltz. This increased physical affection suggests their own emotional intimacy, which they unabashedly display on stage.

This scene is mirrored again at the end of the wedding: Vito leads his daughter through the crowd of clapping attendees, clutching her hand tightly. Holding hands is a sign of affection often seen between a parent and a young child, and in this context the meaning is still valid—perhaps even more so due to Connie’s older age and the likelihood that they no longer are so physically close. As Vito carefully lays his hand on her waist and they begin to waltz, Connie speaks inaudibly to him, causing them both to smile. When the scene cuts to a shot farther away from the two, Connie hugs him tightly as they continue their waltz. This increased physical affection suggests their own emotional intimacy, which they unabashedly display on stage. Instead of greeting Michael with care and love—as Tom Hagen does when he first sees Michael, and as an older brother should do after not having seen his younger brother in quite some time—Fredo flicks the back of Michael’s head. While this gesture suggests a kind of playful intimacy, it underscores Fredo’s immaturity and inability to socialize with people in a more dignified way. The blocking of the action in the scene—with Fredo kneeling between Michael and Kay—also conveys his awkwardness and divisiveness. Michael’s act of bringing Kay to the wedding shows his devotion to her and telegraphs that one day, they too might get married. When Fredo sits between them, he separates the two and effectively disrupts the natural state of the couple.

Instead of greeting Michael with care and love—as Tom Hagen does when he first sees Michael, and as an older brother should do after not having seen his younger brother in quite some time—Fredo flicks the back of Michael’s head. While this gesture suggests a kind of playful intimacy, it underscores Fredo’s immaturity and inability to socialize with people in a more dignified way. The blocking of the action in the scene—with Fredo kneeling between Michael and Kay—also conveys his awkwardness and divisiveness. Michael’s act of bringing Kay to the wedding shows his devotion to her and telegraphs that one day, they too might get married. When Fredo sits between them, he separates the two and effectively disrupts the natural state of the couple. Though Sonny Corleone, the oldest son and therefore the eventual successor to the family business, shares few of Fredo’s character traits, he is also unlike his father in both personality and values. His reckless and impulsive nature is dramatized in his interaction with the FBI agents who are documenting, in an act of surveillance, the people who are attending the wedding. After unsuccessfully attempting to get the agents to leave and being met instead with a stoic face and an FBI ID, Sonny takes his frustration out on one of the agents, yanking his camera away and throwing it on the ground. Afterwards, he’s held back by Peter Clemenza; if Clemenza had not been there, Sonny would have likely thrown some punches. Then, in classic gangster fashion, he drops a couple of crumpled bills on the ground to pay for the broken camera.

Though Sonny Corleone, the oldest son and therefore the eventual successor to the family business, shares few of Fredo’s character traits, he is also unlike his father in both personality and values. His reckless and impulsive nature is dramatized in his interaction with the FBI agents who are documenting, in an act of surveillance, the people who are attending the wedding. After unsuccessfully attempting to get the agents to leave and being met instead with a stoic face and an FBI ID, Sonny takes his frustration out on one of the agents, yanking his camera away and throwing it on the ground. Afterwards, he’s held back by Peter Clemenza; if Clemenza had not been there, Sonny would have likely thrown some punches. Then, in classic gangster fashion, he drops a couple of crumpled bills on the ground to pay for the broken camera. This moment from the wedding scene encapsulates well the cruelty of the irony. His wife is in the foreground, busy talking to other guests and joking about the size of his phallus—which in its own way is a form of endearment. Meanwhile Sonny is almost directly behind her, just having whispered into the bridesmaid’s ear to meet him in a more private setting. He is cheating on his wife literally behind her back, and her close proximity to him while he commits this act suggests how normal this sort of betrayal has become for him. He puts a little care into hiding his unfaithfulness, but his suspicious activities are not unnoticed by his wife, who looks behind her to find him, only to see that he is already gone.

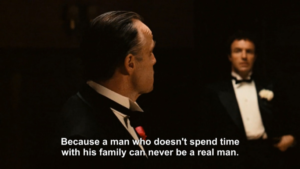

This moment from the wedding scene encapsulates well the cruelty of the irony. His wife is in the foreground, busy talking to other guests and joking about the size of his phallus—which in its own way is a form of endearment. Meanwhile Sonny is almost directly behind her, just having whispered into the bridesmaid’s ear to meet him in a more private setting. He is cheating on his wife literally behind her back, and her close proximity to him while he commits this act suggests how normal this sort of betrayal has become for him. He puts a little care into hiding his unfaithfulness, but his suspicious activities are not unnoticed by his wife, who looks behind her to find him, only to see that he is already gone. While talking to Johnny Fontane, he asks him if he spends time with his family, which Johnny replies affirmatively to. He follows up with a bit of moral instruction—“Because a man who doesn’t spend time with his family can never be a real man”—and here he looks directly at Sonny, directing the line more to him than to Johnny. Vito doesn’t address the issue in a private one-on-one, but he doesn’t need to, as this line serves as his condemnation of Sonny’s act. And in this condemnation, he embarrasses his son for failing to be a “real man” and a proper Corleone father.

While talking to Johnny Fontane, he asks him if he spends time with his family, which Johnny replies affirmatively to. He follows up with a bit of moral instruction—“Because a man who doesn’t spend time with his family can never be a real man”—and here he looks directly at Sonny, directing the line more to him than to Johnny. Vito doesn’t address the issue in a private one-on-one, but he doesn’t need to, as this line serves as his condemnation of Sonny’s act. And in this condemnation, he embarrasses his son for failing to be a “real man” and a proper Corleone father. While Michael may not be as immature as his two older brothers, the moment he walks into the wedding a distinction is already made between him and the rest of his family. As he walks into the estate with Kay, noticeably late—13 minutes already into the film to be exact—his military uniform sticks out like a sore thumb. Michael makes deliberate choices to differentiate himself from the rest of the Corleone family, showing up when he wants to instead of at the beginning of the wedding, wearing what he wants to instead of a tuxedo like the rest of his brothers, and bringing a non-Italian-American date (who herself chooses to wear a dress that is Americana in style). These choices construct his character as just another attendee and not a central member of the Corleone family. In his first interaction with a member of the family, Michael hears from Tom that his father is looking for him.

While Michael may not be as immature as his two older brothers, the moment he walks into the wedding a distinction is already made between him and the rest of his family. As he walks into the estate with Kay, noticeably late—13 minutes already into the film to be exact—his military uniform sticks out like a sore thumb. Michael makes deliberate choices to differentiate himself from the rest of the Corleone family, showing up when he wants to instead of at the beginning of the wedding, wearing what he wants to instead of a tuxedo like the rest of his brothers, and bringing a non-Italian-American date (who herself chooses to wear a dress that is Americana in style). These choices construct his character as just another attendee and not a central member of the Corleone family. In his first interaction with a member of the family, Michael hears from Tom that his father is looking for him. Coppola cuts to a close-up shot here, placing emphasis on both the importance of the statement as well as the secrecy of it—as it is family business—to ensure that Kay will not overhear. But Michael barely reciprocates, simply nodding before sitting back down to continue dining with Kay. This is a direct rejection of Vito, and more generally a rejection of any effort to craft stronger ties with his family and the dubious business they deal in.

Coppola cuts to a close-up shot here, placing emphasis on both the importance of the statement as well as the secrecy of it—as it is family business—to ensure that Kay will not overhear. But Michael barely reciprocates, simply nodding before sitting back down to continue dining with Kay. This is a direct rejection of Vito, and more generally a rejection of any effort to craft stronger ties with his family and the dubious business they deal in. Michael’s decision to create a strong distinction between himself and his family is epitomized in a later scene in which he recounts the story of how Vito helped launch Johnny’s solo career. As he relates Vito’s criminal activities to Kay in vivid detail, he ends with the line “That’s my family Kay. It’s not me.” Michael makes it clear to Kay that he no longer feels a sense of belonging within his own family. It appears that Michael, decked out in his military uniform, is attempting to rebrand himself as a law-abiding, patriotic citizen — the exact opposite of a Corleone.

Michael’s decision to create a strong distinction between himself and his family is epitomized in a later scene in which he recounts the story of how Vito helped launch Johnny’s solo career. As he relates Vito’s criminal activities to Kay in vivid detail, he ends with the line “That’s my family Kay. It’s not me.” Michael makes it clear to Kay that he no longer feels a sense of belonging within his own family. It appears that Michael, decked out in his military uniform, is attempting to rebrand himself as a law-abiding, patriotic citizen — the exact opposite of a Corleone. Furthermore, we can see that, outside of his decisions to distance himself from the family, Michael is still a bearer of Sicilian values and culture: he talks about Sicilian family titles, recounts stories regarding his father, and even waltzes with his significant other, much like Vito is seen doing at various points in the wedding.

Furthermore, we can see that, outside of his decisions to distance himself from the family, Michael is still a bearer of Sicilian values and culture: he talks about Sicilian family titles, recounts stories regarding his father, and even waltzes with his significant other, much like Vito is seen doing at various points in the wedding.

As the head of the Family, Vito is not stripped of his patriarchal position when he sits down. Rather, his status is elevated: he is a king upon his throne. With all eyes drawn toward him, he is careful to use limited and deliberate physical gestures to conceal his thoughts and emotions. When Tom Hagen briefs Vito about Sollozzo’s request to receive protection in exchange for a percentage of the profits of his drug trade, Vito sits with his legs crossed while reclining in his seat. Before the meeting with Sollozzo commences, Vito nods his head, shrugs his shoulders, and sways—as if he were doing Sollozzo a favor by indulging his offer, only bestowing the minimum physical attention required to hear his request. He also asks Tom if he is “not too tired,” as if to suggest his own fatigue as the Don. His body language reveals a disinclination towards stretching the reach of the Family business, as it jeopardizes the familial affiliations that he has established within and outside his blood ties. When Sonny asks him what his decision is going to be, Vito raises his hand from his cheek before resting it on his chin, withholding his thoughts until the next scene.

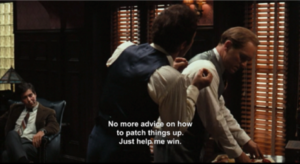

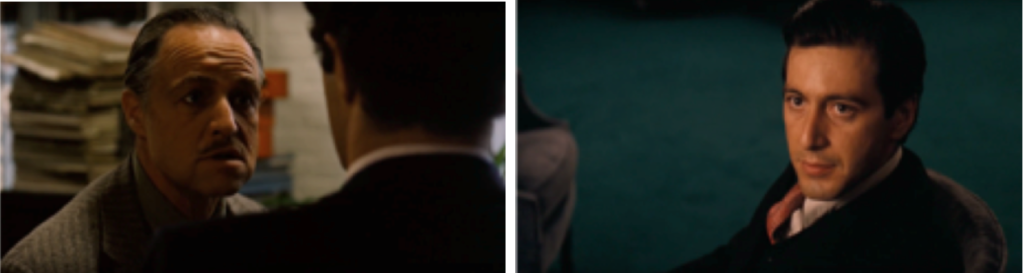

As the head of the Family, Vito is not stripped of his patriarchal position when he sits down. Rather, his status is elevated: he is a king upon his throne. With all eyes drawn toward him, he is careful to use limited and deliberate physical gestures to conceal his thoughts and emotions. When Tom Hagen briefs Vito about Sollozzo’s request to receive protection in exchange for a percentage of the profits of his drug trade, Vito sits with his legs crossed while reclining in his seat. Before the meeting with Sollozzo commences, Vito nods his head, shrugs his shoulders, and sways—as if he were doing Sollozzo a favor by indulging his offer, only bestowing the minimum physical attention required to hear his request. He also asks Tom if he is “not too tired,” as if to suggest his own fatigue as the Don. His body language reveals a disinclination towards stretching the reach of the Family business, as it jeopardizes the familial affiliations that he has established within and outside his blood ties. When Sonny asks him what his decision is going to be, Vito raises his hand from his cheek before resting it on his chin, withholding his thoughts until the next scene. After he inherits Vito’s throne, Michael’s sitting posture recalls his father’s — but with some striking differences. When Michael offers a plan to exact retribution for his father’s shooting, he positions himself in an armchair in a similar manner to his father, crossing his legs and lolling in the furniture. However, Michael is not as calm and collected as Vito had been: he rubs his eyebrows and slumps in his chair, moving his body back and forth before proceeding with his plan. He’s restless—sweaty and squirming. He wants to take immediate action, but he does not act upon his impulses. In the following moments, he places both arms on the handles of the chair as a way to ground himself within the turbulence. As the camera zooms in, Michael’s body becomes more relaxed while still tilting forward: we sense that he is more comfortable with his position, prepared to prove his power. He slurs his words, recalling how his father often mumbles his words, but he does so in anger, his gestures intensified by the sternness of his stare and speech.

After he inherits Vito’s throne, Michael’s sitting posture recalls his father’s — but with some striking differences. When Michael offers a plan to exact retribution for his father’s shooting, he positions himself in an armchair in a similar manner to his father, crossing his legs and lolling in the furniture. However, Michael is not as calm and collected as Vito had been: he rubs his eyebrows and slumps in his chair, moving his body back and forth before proceeding with his plan. He’s restless—sweaty and squirming. He wants to take immediate action, but he does not act upon his impulses. In the following moments, he places both arms on the handles of the chair as a way to ground himself within the turbulence. As the camera zooms in, Michael’s body becomes more relaxed while still tilting forward: we sense that he is more comfortable with his position, prepared to prove his power. He slurs his words, recalling how his father often mumbles his words, but he does so in anger, his gestures intensified by the sternness of his stare and speech. Vito and Michael both use hand movements that reveal them suppressing their anger and frustration. In the opening scene, mortician Amerigo Bonasera offers to pay Vito Corleone in exchange for revenge upon the men who abused his daughter—an offer which offends the Don, as it insinuates he is both a killer and can be “bought.” Prior to this exact moment, Vito’s hand is petting and playing with a cat sitting on his lap; just after, his grip tightens around the animal’s head. The sequence of gestures suggests a few meanings: (1) he is crushing his urge to act upon his anger towards Amerigo Bonasera—he is a man, “not a murderer”—which would demonstrate a childish weakness that cannot be associated with the patriarch of a family, let alone the Family; and (2) given that the image of a cat often carries both feminine and sexual connotations, Vito’s intensifying hold shows him flexing his masculine power and exerting his dominance, his full control.

Vito and Michael both use hand movements that reveal them suppressing their anger and frustration. In the opening scene, mortician Amerigo Bonasera offers to pay Vito Corleone in exchange for revenge upon the men who abused his daughter—an offer which offends the Don, as it insinuates he is both a killer and can be “bought.” Prior to this exact moment, Vito’s hand is petting and playing with a cat sitting on his lap; just after, his grip tightens around the animal’s head. The sequence of gestures suggests a few meanings: (1) he is crushing his urge to act upon his anger towards Amerigo Bonasera—he is a man, “not a murderer”—which would demonstrate a childish weakness that cannot be associated with the patriarch of a family, let alone the Family; and (2) given that the image of a cat often carries both feminine and sexual connotations, Vito’s intensifying hold shows him flexing his masculine power and exerting his dominance, his full control. Michael, on the other hand, is less composed and constrained in his physical mannerisms—his body is seemingly riddled with anxiety. After Michael’s return from Sicily, he makes significant decisions as the new “head of the Family,” including relocating the business transactions to Las Vegas and replacing Tom Hagen as consigliere. During this scene, Michael is twiddling a zippo lighter between his fingers, smoking a cigarette, and prolongedly pressing it into an ashtray.

Michael, on the other hand, is less composed and constrained in his physical mannerisms—his body is seemingly riddled with anxiety. After Michael’s return from Sicily, he makes significant decisions as the new “head of the Family,” including relocating the business transactions to Las Vegas and replacing Tom Hagen as consigliere. During this scene, Michael is twiddling a zippo lighter between his fingers, smoking a cigarette, and prolongedly pressing it into an ashtray.

After the opening scene, Don Vito runs a hand against his grey, slicked-backed hair and qualifies his terms for the mortician’s debt: “We’re not murderers, despite what this undertaker says.” In this scene, Vito is literally scratching his head at his decision to expand the scope of the Family to meet the pleas of an acquaintance who has deliberately avoided them. Yet Vito’s grooming habit is second nature to him—he stays in character as the cool and collected Don.

After the opening scene, Don Vito runs a hand against his grey, slicked-backed hair and qualifies his terms for the mortician’s debt: “We’re not murderers, despite what this undertaker says.” In this scene, Vito is literally scratching his head at his decision to expand the scope of the Family to meet the pleas of an acquaintance who has deliberately avoided them. Yet Vito’s grooming habit is second nature to him—he stays in character as the cool and collected Don. This gesture is replayed in a different key in the pivotal scene at the Italian restaurant, in which Michael struggles to carry out the plot he proposed—to kill Sollozzo and his police guard. Just after he retrieves the gun from the restaurant’s toilet, Michael stands in front of the bathroom’s mirror and presses both hands against his hair in an attempt to gather himself. Here, Michael is on the edge of becoming a part of the family — a family that he had pointedly described, to his girlfriend Kay, as “not me”. His fingers are pushed against his head—he is trying to wrap his brain around his decision. By executing his plan, he not only will be initiated into the business, but also will finally be able to feel like a part of the Corleone family by embodying the role of his father. With the gun concealed in his jacket, Michael seats himself at the table with Sollozzo and his police guard; he brushes his hair back and switches from speaking in Italian to English when staking his claim: “What’s most important to me is that I have a guarantee: no more attempts on my father’s life.” By protecting the patriarch, Michael secures his succession.

This gesture is replayed in a different key in the pivotal scene at the Italian restaurant, in which Michael struggles to carry out the plot he proposed—to kill Sollozzo and his police guard. Just after he retrieves the gun from the restaurant’s toilet, Michael stands in front of the bathroom’s mirror and presses both hands against his hair in an attempt to gather himself. Here, Michael is on the edge of becoming a part of the family — a family that he had pointedly described, to his girlfriend Kay, as “not me”. His fingers are pushed against his head—he is trying to wrap his brain around his decision. By executing his plan, he not only will be initiated into the business, but also will finally be able to feel like a part of the Corleone family by embodying the role of his father. With the gun concealed in his jacket, Michael seats himself at the table with Sollozzo and his police guard; he brushes his hair back and switches from speaking in Italian to English when staking his claim: “What’s most important to me is that I have a guarantee: no more attempts on my father’s life.” By protecting the patriarch, Michael secures his succession. When Vito meets with Sollozzo to listen to his proposition (only to decline), his blazer is unbuttoned, and he droops one arm over the chair while the other dangles from his hip. Vito gives the appearance of approachability while still upholding his authority—he does not need to exercise his dominance in the situation because his mere presence is enough. Vito’s amiability is not so much a sign of respect for Sollozzo, but a means of maintaining respectability as a representative of the Corleone tribe. As Vito turns down Sollozzo’s request, his hands are clasped, but not fastened together, and he strokes and shrugs his thumbs: “It doesn’t make any difference to me what a man does for a living.” Vito is not interested in what can be done to advance his enterprise, but in what he can do to preserve the relationships with his current business partners.

When Vito meets with Sollozzo to listen to his proposition (only to decline), his blazer is unbuttoned, and he droops one arm over the chair while the other dangles from his hip. Vito gives the appearance of approachability while still upholding his authority—he does not need to exercise his dominance in the situation because his mere presence is enough. Vito’s amiability is not so much a sign of respect for Sollozzo, but a means of maintaining respectability as a representative of the Corleone tribe. As Vito turns down Sollozzo’s request, his hands are clasped, but not fastened together, and he strokes and shrugs his thumbs: “It doesn’t make any difference to me what a man does for a living.” Vito is not interested in what can be done to advance his enterprise, but in what he can do to preserve the relationships with his current business partners. Michael is not as gentle, however, when he arrives in Las Vegas to buy Moe Greene’s casino and offer Johnny Fontaine a new contract. In this scene, Michael clasps his hands as well, except with his thumbs pressed together. Not only is he steadfast in his position, but also he’s confident that no one in the room can “refuse” him nor the strength he flexes. Moe Greene then barges in and argues with Michael over the notion that he can “buy [him] out,” and Fredo defends Moe and questions Michael’s reasoning. Echoing the earlier scene in which his father advised Sonny to “never tell anyone outside the family what [he thinks] again,” Michael warns Fredo never to “take sides with anyone against the family again.”

Michael is not as gentle, however, when he arrives in Las Vegas to buy Moe Greene’s casino and offer Johnny Fontaine a new contract. In this scene, Michael clasps his hands as well, except with his thumbs pressed together. Not only is he steadfast in his position, but also he’s confident that no one in the room can “refuse” him nor the strength he flexes. Moe Greene then barges in and argues with Michael over the notion that he can “buy [him] out,” and Fredo defends Moe and questions Michael’s reasoning. Echoing the earlier scene in which his father advised Sonny to “never tell anyone outside the family what [he thinks] again,” Michael warns Fredo never to “take sides with anyone against the family again.”

In their final interaction in the film, Michael is already Don of the Family and Vito is “retired.” The viewer can sense a shift in Vito’s demeanor; he is smiling, joking, drinking wine, and sitting with his right leg folded above the other. He is not hunched over, as he had been in many previous scenes. The burden of the Family business has been removed from his shoulders, and he can take it easy, if only for an instant.

In their final interaction in the film, Michael is already Don of the Family and Vito is “retired.” The viewer can sense a shift in Vito’s demeanor; he is smiling, joking, drinking wine, and sitting with his right leg folded above the other. He is not hunched over, as he had been in many previous scenes. The burden of the Family business has been removed from his shoulders, and he can take it easy, if only for an instant. Tellingly, when Vito positions himself in his seat, he obscures the image of Michael. The camera work suggests how succession works in this family: the importance of the patriarch means that there’s no room for others, just the single male head. To be powerful, to be head of the family: this aspiration is tied to Michael becoming singular, with a way of moving his body that—however indebted to his father—is his and his alone.

Tellingly, when Vito positions himself in his seat, he obscures the image of Michael. The camera work suggests how succession works in this family: the importance of the patriarch means that there’s no room for others, just the single male head. To be powerful, to be head of the family: this aspiration is tied to Michael becoming singular, with a way of moving his body that—however indebted to his father—is his and his alone.