“Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli”: The Hit Man as Family Man

By Sterling Farrance

In a film as eminently quotable as Coppola’s The Godfather, perhaps only one choice line emerged solely from improvisation: “Leave the gun. Take the cannoli.” Neither the shooting script nor the novel mentions cannolis, but Coppola had his own childhood memories to draw this detail from: he remembered the specific white boxes that his father would bring home after work. That said, it was not Coppola who generated the line: Clemenza’s “Take the cannoli” line was an improvisation on the part of actor Richard Castellano, who portrayed him. The line became the favorite of many of The Godfather’s cast and crew, including Michael Chapman, a cameraman who would later, as cinematographer, become famous for his work on Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, among other great films. (The Annotated Godfather)

While the history behind this little tidbit of Hollywood magic is indeed fascinating, the line itself stands out because, in tandem with the scenes around it, it condenses so much about the values on display in The Godfather: in the world of the Corleones, family comes before all else, protecting children is imperative, and business is business.

***

Peter Clemenza has been assigned the grim duty of assuring that Paulie is punished for the attack on Vito Corleone, and this is where the sequence leading up to the cannolis begins. In this first scene, we see Clemenza’s smaller family unit and get a sense of his home life. This short sequence personalizes the larger mob family and conveys many of the themes found in the film: the immigrant dream of American middle-class bliss, the need to care for and protect the family, and the untrustworthy and false front of business. Clemenza’s home is cozy, and seemingly of the type to be found in a place like Long Island. There are kids playing in the street and driveway, and we can hear laughter and joyous voices. The car that’s parked in the driveway is postwar and is shiny and gorgeous. Strife is conspicuously absent here; Clemenza’s home life is warm, and even idyllic. This seems to be the very life that Vito left Sicily for.

The camera cuts in to the doorstep, and Clemenza talks with his wife. They speak in the rhythm of a couple married for many years. Clemenza has his back turned to the camera, so his wife’s face, dialogue, and motions grab our attention, just as she is trying to grab her husband’s attention before he leaves for work. She wants to know when he’ll be home, and lovingly blows him a kiss after he tells her it will be late. She smiles after him as he walks away, as if to say “what a good man, what a good life I have.” To her, it’s just another day and nothing in Clemenza’s demeanor has given away that he’s on a brutal mission. He’s already in character, already putting up the false front he must maintain to deflect Paulie’s suspicion and keep the hit moving smoothly.

As he climbs into the car, she calls after him “Don’t forget the cannoli!” Clemenza replies, “Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.” We tend to want to chuckle a bit, or at least smile: his repeated “yeahs” seem to convey “Oh that wife, how she nags, but she’s really a good one, and I love her, and won’t forget those cannolis.” But the humdrum dialogue not only personalizes this family unit, and through extension the larger Corleone mob family, but also suggests the importance of a certain level of comfort, of the pleasure that comes with that comfort. In the American dream of prosperity, it’s not enough simply to feed your family; one needs the treats that come from keeping that slightly more privileged existence.

As Clemenza sits in the car, Paulie’s anxiety is readily apparent. He nervously looks at Rocco in the back seat and tells him to move, explaining that he needs a better view of the car’s rear. Paulie is fooling nobody, but this doesn’t matter. Clemenza doesn’t even show that he’s noticed, and Rocco moves without comment. Paulie is no actor, while Clemenza has a cold and routine manner. This is what’s needed to protect the family, and to keep the business moving. As they begin to pull out of the driveway, Clemenza sternly warns Paulie to “watch out for the kids while you’re backing out.” Like Vito who cares so deeply about the welfare of his children, Clemenza, even in moments of intense focus and responsibility, is looking out for his own children.

***

Notably, this unflinching drive to protect the family is exactly what led us to this scene in the first place. Paulie has seemingly betrayed Vito—and thus the family—by selling him out. In The Godfather, this kind of betrayal is the worst of all sins. We see the matter discussed, in the Corleone family office, just before the viewer spends time in front of Clemenza’s cozy abode.

In the middle of deliberations about the fate of the family, Paulie enters the room with a message, handkerchief in hand, coughing a very pitifully fake sounding cough. Sonny sees through this faux-illness and doesn’t believe it’s a coincidence that Vito was shot the day Paulie was “sick.” Paulie, meanwhile, seems to foolishly think the family has gone soft enough not to catch him, but his poor acting underscores that he doesn’t have what it takes to handle the business world of the film. As soon as Paulie leaves the room, Sonny sternly orders the hit, telling Clemenza to make it the first thing on his list. Not only is betrayal the worst of all sins, necessitating an immediate death sentence, but there can be no time wasted.

***

Clemenza is just the man to enact the necessary care and protection of the family. Beneath Clemenza’s calm exterior, he is calculating—planning and taking precise action. Before Clemenza, Rocco, and Paulie have even left his driveway, Clemenza starts planning. The family business must move much quicker than before to deal with the myriad problems arising from the shooting of the Don. Clemenza begins discussing arrangements for safehouses to protect the family. This begins to settle Paulie down a bit.

Though this planning might ease Paulie’s anxiety, it is also legitimate, and is in fact critical work. On the level of the plot, it makes Paulie feel comfortable and gives him the sense that business is running as usual, which will keep the hit running smoothly, with no struggle or risk of the attempt being thwarted. Rocco, who sits in the back seat ready to actually commit the murder, is also being groomed to take Paulie’s place. While Clemenza lays out safehouse instructions throughout the drive, he might as well be giving this information to Rocco. They can’t just waste the time it takes to drive to a rural place and kill Paulie; they must plan next steps as well. The family business cannot stop or even slow down.

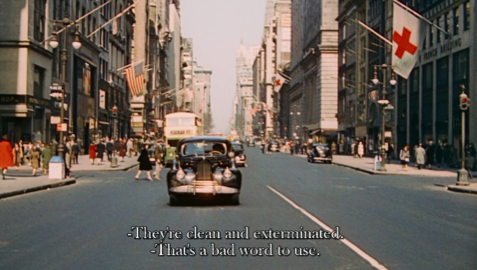

As they drive along, they trade jokes. While these jokes work to lighten the tone with Paulie, they have a deeper subtext too. En route to the remote spot that will serve as the scene of Paulie’s death, Clemenza explains that the mattresses must be clean because they will be in use for a long while. Paulie assures him that they are: “They told me they exterminate them.” Rocco starts to laugh, and Clemenza exclaims, “Exterminate? That’s a bad word to use: exterminate! Get this guy. Watch out we don’t exterminate you!”

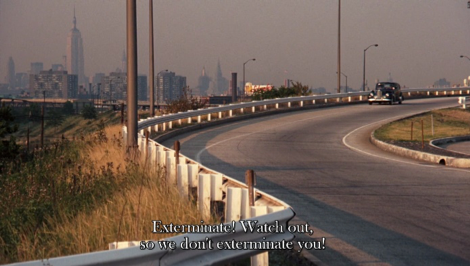

On an instrumental level, Clemenza is keeping things light and jovial to prevent Paulie from suspecting anything: while instructing him to “watch out,” he is in fact disarming him. But this joke has a different level of meaning for viewers who see the hit coming: in light of the murder they have planned, this joke seems incredibly cold, harsh, and calculated. The three of them then joke about flatulence in Italian—a very crude and typical “Who farted? It wasn’t me, it must have been you!” bit of banter. Before the laughter and tone has the chance to shift, Clemenza crudely declares, “Pull over. I’ve got to take a leak.” The tone of the moment continues to be earthy, casual. This of course opens the opportunity for the actual killing, and all the humor has prevented Paulie from becoming too suspicious. He is shot while Clemenza urinates—as if to suggest that the killing is as routine, regular, and necessary as “taking a leak.”

The act itself is done swiftly and coldly while Clemenza urinates. He walks away, unzips, and almost immediately three gunshots are fired. The camera is close to Clemenza, and he turns his head just enough to allow the viewer to see his slight reaction. When the act happens, there is maybe a hint of unexpected sadness that plays over his face, but the dominant look is one of resignation—resignation, we imagine, to the necessity of this act. Meanwhile the camera is incredibly far away from Paulie and Rocco, far enough to keep the act impersonal, and far enough to show us the Statue of Liberty in the distant background. This kind of coldness and decisiveness is what has allowed the family to achieve the safety and the immigrant dream symbolized by that pillar of freedom, and only this cold slaying will allow them to keep it.

Clemenza tells Rocco, “Leave the gun,” which also means leave the car, the bloody body, the shattered windshield, and this whole horrific scene. Leave it to be a message; let it show the family has not gone soft, not gotten sloppy or stupid, and let it show what the cost of betrayal is. And then Clemenza gives the punchline: “take the cannoli.” He cannot leave that prized treat he has promised the family: otherwise what’s this all for? In the world of The Godfather, your word is your bond. He might have pushed away his wife with “Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah,” but he wouldn’t dare forget her beloved cannolis. His conscientiousness lightly suggests the follow-through necessary to survive this film’s world (Michael is expert at follow-through). So Clemenza tells Rocco to reach into the bloody car for the special dessert. He is bringing back the cannoli, but also—thanks to the killing—a safer state for the family, one more secure and without the current threat of betrayal.

We can demonstrate why this scene is so important to the narrative, and we can illuminate how well executed it is; however, we may not have explained why everyone loves that quote. I know I count myself among its fans, but I can’t quite tell you why. I think it has something to do with the economy of its language—how, in the space of six words total, we get two sentences that convey so much about the core of this remarkable film. It’s a straight-up, practical line that advances the story very efficiently. But pure efficiency isn’t what makes great art. You can’t just leave the aesthetics and take the function. The quick rhythm, the parallel structure, and the decisiveness they register are appealing for reasons that go beyond mere efficiency. So maybe that’s why we adore these two quick lines: because they blend form and function at the highest level.

But let’s be real, we’d all be lying to ourselves—at least a little—if we don’t admit: it’s also totally badass.

Sterling Farrance is a writer/educator with a freshly minted B.A. in English and Creative Writing from UC Berkeley. An avid cinephile and lover of anachronistic media, he is looking forward to beginning an MFA at St. Mary’s College in Moraga, California where he will write about how film changes one’s view of the world. This, of course, is mostly just an excuse for him to plow through his ever-growing laserdisc collection for the sake of “research.”

Early in the opening wedding scene of The Godfather, a photographer lines up the Corleone family, preparing a family photo to solemnize the marriage of Constanzia, or Connie, Corleone to Carlo Rizzi. Yet Vito Corleone, the Don of this Sicilian family, notes his youngest son’s absence and so stops the shot from being taken: “We’re not taking the picture without Michael.” A picture is forever, and Vito—the center of the family, and with an especially soft spot for his son Michael—insists that all must be present and all must be willing to play their part. What Vito has created through the Corleone family is represented in its purest and most picturesque form by Connie’s wedding, which is huge, vibrant, and cheerful.

Early in the opening wedding scene of The Godfather, a photographer lines up the Corleone family, preparing a family photo to solemnize the marriage of Constanzia, or Connie, Corleone to Carlo Rizzi. Yet Vito Corleone, the Don of this Sicilian family, notes his youngest son’s absence and so stops the shot from being taken: “We’re not taking the picture without Michael.” A picture is forever, and Vito—the center of the family, and with an especially soft spot for his son Michael—insists that all must be present and all must be willing to play their part. What Vito has created through the Corleone family is represented in its purest and most picturesque form by Connie’s wedding, which is huge, vibrant, and cheerful. In the first shot following Vito’s dealings with Amerigo Bonasera, we glimpse the throng that has assembled for the event: though a tree covers half of the crowd, there are still dozens of visible people milling around, and by placing the camera far from the event, the individual people become a blur and turn into one huge sea of costumed bodies. The image suggests how, to the Corleones, a family should function: though the individuals that make up the larger family business are essential to its workings, they are all under the guise of one group and so are united by that group. Even with a sizable attendance already inside the estate, people can be seen still walking into the courtyard. Everyone, from tiny toddlers to their aging grandparents, must come and pay respects to Connie in this momentous event.

In the first shot following Vito’s dealings with Amerigo Bonasera, we glimpse the throng that has assembled for the event: though a tree covers half of the crowd, there are still dozens of visible people milling around, and by placing the camera far from the event, the individual people become a blur and turn into one huge sea of costumed bodies. The image suggests how, to the Corleones, a family should function: though the individuals that make up the larger family business are essential to its workings, they are all under the guise of one group and so are united by that group. Even with a sizable attendance already inside the estate, people can be seen still walking into the courtyard. Everyone, from tiny toddlers to their aging grandparents, must come and pay respects to Connie in this momentous event. Yet Vito is not just a man who spends a lot of money to make his daughter’s wedding a great celebration; he’s the sort of father who actively shows his care with that money by partaking in the festivities, spending time with his family throughout despite his ongoing business deals behind the scenes. This scene fills the wedding with his attention and care as he dances with his wife in the midst of the crowd. Smiles on their faces, the couple waltz as Vito makes an inaudible comment to his wife that conveys the couple’s agreeable intimacy.

Yet Vito is not just a man who spends a lot of money to make his daughter’s wedding a great celebration; he’s the sort of father who actively shows his care with that money by partaking in the festivities, spending time with his family throughout despite his ongoing business deals behind the scenes. This scene fills the wedding with his attention and care as he dances with his wife in the midst of the crowd. Smiles on their faces, the couple waltz as Vito makes an inaudible comment to his wife that conveys the couple’s agreeable intimacy. This scene is mirrored again at the end of the wedding: Vito leads his daughter through the crowd of clapping attendees, clutching her hand tightly. Holding hands is a sign of affection often seen between a parent and a young child, and in this context the meaning is still valid—perhaps even more so due to Connie’s older age and the likelihood that they no longer are so physically close. As Vito carefully lays his hand on her waist and they begin to waltz, Connie speaks inaudibly to him, causing them both to smile. When the scene cuts to a shot farther away from the two, Connie hugs him tightly as they continue their waltz. This increased physical affection suggests their own emotional intimacy, which they unabashedly display on stage.

This scene is mirrored again at the end of the wedding: Vito leads his daughter through the crowd of clapping attendees, clutching her hand tightly. Holding hands is a sign of affection often seen between a parent and a young child, and in this context the meaning is still valid—perhaps even more so due to Connie’s older age and the likelihood that they no longer are so physically close. As Vito carefully lays his hand on her waist and they begin to waltz, Connie speaks inaudibly to him, causing them both to smile. When the scene cuts to a shot farther away from the two, Connie hugs him tightly as they continue their waltz. This increased physical affection suggests their own emotional intimacy, which they unabashedly display on stage. Instead of greeting Michael with care and love—as Tom Hagen does when he first sees Michael, and as an older brother should do after not having seen his younger brother in quite some time—Fredo flicks the back of Michael’s head. While this gesture suggests a kind of playful intimacy, it underscores Fredo’s immaturity and inability to socialize with people in a more dignified way. The blocking of the action in the scene—with Fredo kneeling between Michael and Kay—also conveys his awkwardness and divisiveness. Michael’s act of bringing Kay to the wedding shows his devotion to her and telegraphs that one day, they too might get married. When Fredo sits between them, he separates the two and effectively disrupts the natural state of the couple.

Instead of greeting Michael with care and love—as Tom Hagen does when he first sees Michael, and as an older brother should do after not having seen his younger brother in quite some time—Fredo flicks the back of Michael’s head. While this gesture suggests a kind of playful intimacy, it underscores Fredo’s immaturity and inability to socialize with people in a more dignified way. The blocking of the action in the scene—with Fredo kneeling between Michael and Kay—also conveys his awkwardness and divisiveness. Michael’s act of bringing Kay to the wedding shows his devotion to her and telegraphs that one day, they too might get married. When Fredo sits between them, he separates the two and effectively disrupts the natural state of the couple. Though Sonny Corleone, the oldest son and therefore the eventual successor to the family business, shares few of Fredo’s character traits, he is also unlike his father in both personality and values. His reckless and impulsive nature is dramatized in his interaction with the FBI agents who are documenting, in an act of surveillance, the people who are attending the wedding. After unsuccessfully attempting to get the agents to leave and being met instead with a stoic face and an FBI ID, Sonny takes his frustration out on one of the agents, yanking his camera away and throwing it on the ground. Afterwards, he’s held back by Peter Clemenza; if Clemenza had not been there, Sonny would have likely thrown some punches. Then, in classic gangster fashion, he drops a couple of crumpled bills on the ground to pay for the broken camera.

Though Sonny Corleone, the oldest son and therefore the eventual successor to the family business, shares few of Fredo’s character traits, he is also unlike his father in both personality and values. His reckless and impulsive nature is dramatized in his interaction with the FBI agents who are documenting, in an act of surveillance, the people who are attending the wedding. After unsuccessfully attempting to get the agents to leave and being met instead with a stoic face and an FBI ID, Sonny takes his frustration out on one of the agents, yanking his camera away and throwing it on the ground. Afterwards, he’s held back by Peter Clemenza; if Clemenza had not been there, Sonny would have likely thrown some punches. Then, in classic gangster fashion, he drops a couple of crumpled bills on the ground to pay for the broken camera. This moment from the wedding scene encapsulates well the cruelty of the irony. His wife is in the foreground, busy talking to other guests and joking about the size of his phallus—which in its own way is a form of endearment. Meanwhile Sonny is almost directly behind her, just having whispered into the bridesmaid’s ear to meet him in a more private setting. He is cheating on his wife literally behind her back, and her close proximity to him while he commits this act suggests how normal this sort of betrayal has become for him. He puts a little care into hiding his unfaithfulness, but his suspicious activities are not unnoticed by his wife, who looks behind her to find him, only to see that he is already gone.

This moment from the wedding scene encapsulates well the cruelty of the irony. His wife is in the foreground, busy talking to other guests and joking about the size of his phallus—which in its own way is a form of endearment. Meanwhile Sonny is almost directly behind her, just having whispered into the bridesmaid’s ear to meet him in a more private setting. He is cheating on his wife literally behind her back, and her close proximity to him while he commits this act suggests how normal this sort of betrayal has become for him. He puts a little care into hiding his unfaithfulness, but his suspicious activities are not unnoticed by his wife, who looks behind her to find him, only to see that he is already gone. While talking to Johnny Fontane, he asks him if he spends time with his family, which Johnny replies affirmatively to. He follows up with a bit of moral instruction—“Because a man who doesn’t spend time with his family can never be a real man”—and here he looks directly at Sonny, directing the line more to him than to Johnny. Vito doesn’t address the issue in a private one-on-one, but he doesn’t need to, as this line serves as his condemnation of Sonny’s act. And in this condemnation, he embarrasses his son for failing to be a “real man” and a proper Corleone father.

While talking to Johnny Fontane, he asks him if he spends time with his family, which Johnny replies affirmatively to. He follows up with a bit of moral instruction—“Because a man who doesn’t spend time with his family can never be a real man”—and here he looks directly at Sonny, directing the line more to him than to Johnny. Vito doesn’t address the issue in a private one-on-one, but he doesn’t need to, as this line serves as his condemnation of Sonny’s act. And in this condemnation, he embarrasses his son for failing to be a “real man” and a proper Corleone father. While Michael may not be as immature as his two older brothers, the moment he walks into the wedding a distinction is already made between him and the rest of his family. As he walks into the estate with Kay, noticeably late—13 minutes already into the film to be exact—his military uniform sticks out like a sore thumb. Michael makes deliberate choices to differentiate himself from the rest of the Corleone family, showing up when he wants to instead of at the beginning of the wedding, wearing what he wants to instead of a tuxedo like the rest of his brothers, and bringing a non-Italian-American date (who herself chooses to wear a dress that is Americana in style). These choices construct his character as just another attendee and not a central member of the Corleone family. In his first interaction with a member of the family, Michael hears from Tom that his father is looking for him.

While Michael may not be as immature as his two older brothers, the moment he walks into the wedding a distinction is already made between him and the rest of his family. As he walks into the estate with Kay, noticeably late—13 minutes already into the film to be exact—his military uniform sticks out like a sore thumb. Michael makes deliberate choices to differentiate himself from the rest of the Corleone family, showing up when he wants to instead of at the beginning of the wedding, wearing what he wants to instead of a tuxedo like the rest of his brothers, and bringing a non-Italian-American date (who herself chooses to wear a dress that is Americana in style). These choices construct his character as just another attendee and not a central member of the Corleone family. In his first interaction with a member of the family, Michael hears from Tom that his father is looking for him. Coppola cuts to a close-up shot here, placing emphasis on both the importance of the statement as well as the secrecy of it—as it is family business—to ensure that Kay will not overhear. But Michael barely reciprocates, simply nodding before sitting back down to continue dining with Kay. This is a direct rejection of Vito, and more generally a rejection of any effort to craft stronger ties with his family and the dubious business they deal in.

Coppola cuts to a close-up shot here, placing emphasis on both the importance of the statement as well as the secrecy of it—as it is family business—to ensure that Kay will not overhear. But Michael barely reciprocates, simply nodding before sitting back down to continue dining with Kay. This is a direct rejection of Vito, and more generally a rejection of any effort to craft stronger ties with his family and the dubious business they deal in. Michael’s decision to create a strong distinction between himself and his family is epitomized in a later scene in which he recounts the story of how Vito helped launch Johnny’s solo career. As he relates Vito’s criminal activities to Kay in vivid detail, he ends with the line “That’s my family Kay. It’s not me.” Michael makes it clear to Kay that he no longer feels a sense of belonging within his own family. It appears that Michael, decked out in his military uniform, is attempting to rebrand himself as a law-abiding, patriotic citizen — the exact opposite of a Corleone.

Michael’s decision to create a strong distinction between himself and his family is epitomized in a later scene in which he recounts the story of how Vito helped launch Johnny’s solo career. As he relates Vito’s criminal activities to Kay in vivid detail, he ends with the line “That’s my family Kay. It’s not me.” Michael makes it clear to Kay that he no longer feels a sense of belonging within his own family. It appears that Michael, decked out in his military uniform, is attempting to rebrand himself as a law-abiding, patriotic citizen — the exact opposite of a Corleone. Furthermore, we can see that, outside of his decisions to distance himself from the family, Michael is still a bearer of Sicilian values and culture: he talks about Sicilian family titles, recounts stories regarding his father, and even waltzes with his significant other, much like Vito is seen doing at various points in the wedding.

Furthermore, we can see that, outside of his decisions to distance himself from the family, Michael is still a bearer of Sicilian values and culture: he talks about Sicilian family titles, recounts stories regarding his father, and even waltzes with his significant other, much like Vito is seen doing at various points in the wedding.