“Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli”: The Hit Man as Family Man

By Sterling Farrance

In a film as eminently quotable as Coppola’s The Godfather, perhaps only one choice line emerged solely from improvisation: “Leave the gun. Take the cannoli.” Neither the shooting script nor the novel mentions cannolis, but Coppola had his own childhood memories to draw this detail from: he remembered the specific white boxes that his father would bring home after work. That said, it was not Coppola who generated the line: Clemenza’s “Take the cannoli” line was an improvisation on the part of actor Richard Castellano, who portrayed him. The line became the favorite of many of The Godfather’s cast and crew, including Michael Chapman, a cameraman who would later, as cinematographer, become famous for his work on Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, among other great films. (The Annotated Godfather)

While the history behind this little tidbit of Hollywood magic is indeed fascinating, the line itself stands out because, in tandem with the scenes around it, it condenses so much about the values on display in The Godfather: in the world of the Corleones, family comes before all else, protecting children is imperative, and business is business.

***

Peter Clemenza has been assigned the grim duty of assuring that Paulie is punished for the attack on Vito Corleone, and this is where the sequence leading up to the cannolis begins. In this first scene, we see Clemenza’s smaller family unit and get a sense of his home life. This short sequence personalizes the larger mob family and conveys many of the themes found in the film: the immigrant dream of American middle-class bliss, the need to care for and protect the family, and the untrustworthy and false front of business. Clemenza’s home is cozy, and seemingly of the type to be found in a place like Long Island. There are kids playing in the street and driveway, and we can hear laughter and joyous voices. The car that’s parked in the driveway is postwar and is shiny and gorgeous. Strife is conspicuously absent here; Clemenza’s home life is warm, and even idyllic. This seems to be the very life that Vito left Sicily for.

The camera cuts in to the doorstep, and Clemenza talks with his wife. They speak in the rhythm of a couple married for many years. Clemenza has his back turned to the camera, so his wife’s face, dialogue, and motions grab our attention, just as she is trying to grab her husband’s attention before he leaves for work. She wants to know when he’ll be home, and lovingly blows him a kiss after he tells her it will be late. She smiles after him as he walks away, as if to say “what a good man, what a good life I have.” To her, it’s just another day and nothing in Clemenza’s demeanor has given away that he’s on a brutal mission. He’s already in character, already putting up the false front he must maintain to deflect Paulie’s suspicion and keep the hit moving smoothly.

As he climbs into the car, she calls after him “Don’t forget the cannoli!” Clemenza replies, “Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.” We tend to want to chuckle a bit, or at least smile: his repeated “yeahs” seem to convey “Oh that wife, how she nags, but she’s really a good one, and I love her, and won’t forget those cannolis.” But the humdrum dialogue not only personalizes this family unit, and through extension the larger Corleone mob family, but also suggests the importance of a certain level of comfort, of the pleasure that comes with that comfort. In the American dream of prosperity, it’s not enough simply to feed your family; one needs the treats that come from keeping that slightly more privileged existence.

As Clemenza sits in the car, Paulie’s anxiety is readily apparent. He nervously looks at Rocco in the back seat and tells him to move, explaining that he needs a better view of the car’s rear. Paulie is fooling nobody, but this doesn’t matter. Clemenza doesn’t even show that he’s noticed, and Rocco moves without comment. Paulie is no actor, while Clemenza has a cold and routine manner. This is what’s needed to protect the family, and to keep the business moving. As they begin to pull out of the driveway, Clemenza sternly warns Paulie to “watch out for the kids while you’re backing out.” Like Vito who cares so deeply about the welfare of his children, Clemenza, even in moments of intense focus and responsibility, is looking out for his own children.

***

Notably, this unflinching drive to protect the family is exactly what led us to this scene in the first place. Paulie has seemingly betrayed Vito—and thus the family—by selling him out. In The Godfather, this kind of betrayal is the worst of all sins. We see the matter discussed, in the Corleone family office, just before the viewer spends time in front of Clemenza’s cozy abode.

In the middle of deliberations about the fate of the family, Paulie enters the room with a message, handkerchief in hand, coughing a very pitifully fake sounding cough. Sonny sees through this faux-illness and doesn’t believe it’s a coincidence that Vito was shot the day Paulie was “sick.” Paulie, meanwhile, seems to foolishly think the family has gone soft enough not to catch him, but his poor acting underscores that he doesn’t have what it takes to handle the business world of the film. As soon as Paulie leaves the room, Sonny sternly orders the hit, telling Clemenza to make it the first thing on his list. Not only is betrayal the worst of all sins, necessitating an immediate death sentence, but there can be no time wasted.

***

Clemenza is just the man to enact the necessary care and protection of the family. Beneath Clemenza’s calm exterior, he is calculating—planning and taking precise action. Before Clemenza, Rocco, and Paulie have even left his driveway, Clemenza starts planning. The family business must move much quicker than before to deal with the myriad problems arising from the shooting of the Don. Clemenza begins discussing arrangements for safehouses to protect the family. This begins to settle Paulie down a bit.

Though this planning might ease Paulie’s anxiety, it is also legitimate, and is in fact critical work. On the level of the plot, it makes Paulie feel comfortable and gives him the sense that business is running as usual, which will keep the hit running smoothly, with no struggle or risk of the attempt being thwarted. Rocco, who sits in the back seat ready to actually commit the murder, is also being groomed to take Paulie’s place. While Clemenza lays out safehouse instructions throughout the drive, he might as well be giving this information to Rocco. They can’t just waste the time it takes to drive to a rural place and kill Paulie; they must plan next steps as well. The family business cannot stop or even slow down.

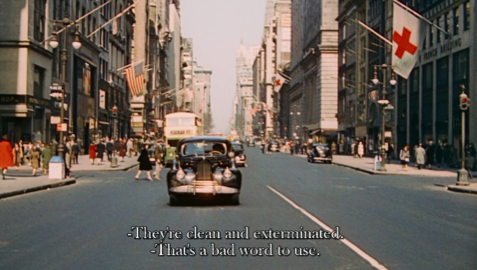

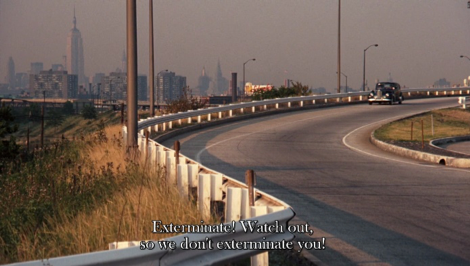

As they drive along, they trade jokes. While these jokes work to lighten the tone with Paulie, they have a deeper subtext too. En route to the remote spot that will serve as the scene of Paulie’s death, Clemenza explains that the mattresses must be clean because they will be in use for a long while. Paulie assures him that they are: “They told me they exterminate them.” Rocco starts to laugh, and Clemenza exclaims, “Exterminate? That’s a bad word to use: exterminate! Get this guy. Watch out we don’t exterminate you!”

On an instrumental level, Clemenza is keeping things light and jovial to prevent Paulie from suspecting anything: while instructing him to “watch out,” he is in fact disarming him. But this joke has a different level of meaning for viewers who see the hit coming: in light of the murder they have planned, this joke seems incredibly cold, harsh, and calculated. The three of them then joke about flatulence in Italian—a very crude and typical “Who farted? It wasn’t me, it must have been you!” bit of banter. Before the laughter and tone has the chance to shift, Clemenza crudely declares, “Pull over. I’ve got to take a leak.” The tone of the moment continues to be earthy, casual. This of course opens the opportunity for the actual killing, and all the humor has prevented Paulie from becoming too suspicious. He is shot while Clemenza urinates—as if to suggest that the killing is as routine, regular, and necessary as “taking a leak.”

The act itself is done swiftly and coldly while Clemenza urinates. He walks away, unzips, and almost immediately three gunshots are fired. The camera is close to Clemenza, and he turns his head just enough to allow the viewer to see his slight reaction. When the act happens, there is maybe a hint of unexpected sadness that plays over his face, but the dominant look is one of resignation—resignation, we imagine, to the necessity of this act. Meanwhile the camera is incredibly far away from Paulie and Rocco, far enough to keep the act impersonal, and far enough to show us the Statue of Liberty in the distant background. This kind of coldness and decisiveness is what has allowed the family to achieve the safety and the immigrant dream symbolized by that pillar of freedom, and only this cold slaying will allow them to keep it.

Clemenza tells Rocco, “Leave the gun,” which also means leave the car, the bloody body, the shattered windshield, and this whole horrific scene. Leave it to be a message; let it show the family has not gone soft, not gotten sloppy or stupid, and let it show what the cost of betrayal is. And then Clemenza gives the punchline: “take the cannoli.” He cannot leave that prized treat he has promised the family: otherwise what’s this all for? In the world of The Godfather, your word is your bond. He might have pushed away his wife with “Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah,” but he wouldn’t dare forget her beloved cannolis. His conscientiousness lightly suggests the follow-through necessary to survive this film’s world (Michael is expert at follow-through). So Clemenza tells Rocco to reach into the bloody car for the special dessert. He is bringing back the cannoli, but also—thanks to the killing—a safer state for the family, one more secure and without the current threat of betrayal.

We can demonstrate why this scene is so important to the narrative, and we can illuminate how well executed it is; however, we may not have explained why everyone loves that quote. I know I count myself among its fans, but I can’t quite tell you why. I think it has something to do with the economy of its language—how, in the space of six words total, we get two sentences that convey so much about the core of this remarkable film. It’s a straight-up, practical line that advances the story very efficiently. But pure efficiency isn’t what makes great art. You can’t just leave the aesthetics and take the function. The quick rhythm, the parallel structure, and the decisiveness they register are appealing for reasons that go beyond mere efficiency. So maybe that’s why we adore these two quick lines: because they blend form and function at the highest level.

But let’s be real, we’d all be lying to ourselves—at least a little—if we don’t admit: it’s also totally badass.

Sterling Farrance is a writer/educator with a freshly minted B.A. in English and Creative Writing from UC Berkeley. An avid cinephile and lover of anachronistic media, he is looking forward to beginning an MFA at St. Mary’s College in Moraga, California where he will write about how film changes one’s view of the world. This, of course, is mostly just an excuse for him to plow through his ever-growing laserdisc collection for the sake of “research.”