Ripeness Is All: The Death of Vito Corleone

By Daniel Arias

Late in The Godfather, when Vito Corleone collapses to the ground and his grandson Anthony runs away to get help, viewers are left to look at the former Don’s body lying motionless in the shade of a trellised tomato garden. For five seconds, the only sounds that fill the soundtrack are the birds chirping and the wind blowing through the trees; then the image fades and funeral bells ring in the next scene. Unlike other critical scenes in the film, which rely on dramatic sequence and action, or intriguing dialogue between characters, this scene has a different way of registering with the viewer: its significance is encapsulated in the symbolic images that frame Vito’s final moments and the non-verbal gestures shared between Vito and his grandson.

Late in The Godfather, when Vito Corleone collapses to the ground and his grandson Anthony runs away to get help, viewers are left to look at the former Don’s body lying motionless in the shade of a trellised tomato garden. For five seconds, the only sounds that fill the soundtrack are the birds chirping and the wind blowing through the trees; then the image fades and funeral bells ring in the next scene. Unlike other critical scenes in the film, which rely on dramatic sequence and action, or intriguing dialogue between characters, this scene has a different way of registering with the viewer: its significance is encapsulated in the symbolic images that frame Vito’s final moments and the non-verbal gestures shared between Vito and his grandson.

It is no accident that the central prop of this scene is a watering gun — an implement which evokes power and the potential for violence but does so lightly, even ironically. (Water, not bullets, issue from its ‘barrel’.) Just before this scene, Vito speaks to his son, Michael, in the same garden. In that scene, Vito grapples with the guilt and uncertainty of having to transfer his power down to the next generation. Handing his status and the family business to Michael, he wants also to advise his son and ensure that the business can flourish. Though Michael is not unkind with Vito, neither is he overly deferential: the scene signals clearly that Michael, as the new Don, will make his own decisions.

It is no accident that the central prop of this scene is a watering gun — an implement which evokes power and the potential for violence but does so lightly, even ironically. (Water, not bullets, issue from its ‘barrel’.) Just before this scene, Vito speaks to his son, Michael, in the same garden. In that scene, Vito grapples with the guilt and uncertainty of having to transfer his power down to the next generation. Handing his status and the family business to Michael, he wants also to advise his son and ensure that the business can flourish. Though Michael is not unkind with Vito, neither is he overly deferential: the scene signals clearly that Michael, as the new Don, will make his own decisions.

This power dynamic is reenacted in the garden scene when Vito hands his grandson the watering gun. As a fatigued old grandfather, Vito can no longer stand for too long and he must sit down to watch Anthony play. From this position, Vito still seeks out any control he might have, shouting at his grandson, “over her, over here. Be careful, you’re spilling it, you’re spilling it. Anthony, come here, come here. Come here.” In the same way that he cannot control how Michael runs the family business, Vito cannot control how Anthony uses the water gun to feed the tomato vines. He has passed down the power to the new generation of his family: how they use that power, and how it affects them, are completely out of his control.

***

Vito Corleone’s loss of power is reflected in his physical appearance and presentation. In the introductory scene of the film, Vito comes across as a powerful figure. His words carry weight and deliberation in his monologue; he wears a fine suit, and his hair neatly slicked back. By contrast, this scene presents Vito in casual clothing, and with unruly hair protruding out of his hat. His body appears languid and shriveled by age. It is a portrait of a powerless Don. Even the simple act of calling out to his grandson and extending his arm as gesture seems like an extra strain on his body.

Vito Corleone’s loss of power is reflected in his physical appearance and presentation. In the introductory scene of the film, Vito comes across as a powerful figure. His words carry weight and deliberation in his monologue; he wears a fine suit, and his hair neatly slicked back. By contrast, this scene presents Vito in casual clothing, and with unruly hair protruding out of his hat. His body appears languid and shriveled by age. It is a portrait of a powerless Don. Even the simple act of calling out to his grandson and extending his arm as gesture seems like an extra strain on his body.

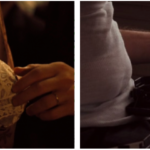

The only gesture of power that Vito conveys in this scene is reliant on artifice. To get his grandson’s attention, Vito cuts an orange peel and fashions a pair of fangs for his mouth. In his final exertion of power before he dies, he pretends to be a big and scary monster to frighten his grandson. The performance of power is what leads to his death — both literally, in this scene, and symbolically for the overall story arc of his character. Through much of the film, Vito has performed the role of mafia Don as the ultimate exertion of his power, but in this scene, viewers are offered a glimpse into what Vito Corleone looks like without his presentation and appearance as the powerful Don Corleone. When he adorns himself with a pair of fangs, to play pretend with his grandson, the scene frames the gesture as a representation of how Vito performs throughout the film; the only difference here is that viewers witness the process of how Vito transforms himself to convey power, even if it is just to frighten his grandson for a brief moment.

The only gesture of power that Vito conveys in this scene is reliant on artifice. To get his grandson’s attention, Vito cuts an orange peel and fashions a pair of fangs for his mouth. In his final exertion of power before he dies, he pretends to be a big and scary monster to frighten his grandson. The performance of power is what leads to his death — both literally, in this scene, and symbolically for the overall story arc of his character. Through much of the film, Vito has performed the role of mafia Don as the ultimate exertion of his power, but in this scene, viewers are offered a glimpse into what Vito Corleone looks like without his presentation and appearance as the powerful Don Corleone. When he adorns himself with a pair of fangs, to play pretend with his grandson, the scene frames the gesture as a representation of how Vito performs throughout the film; the only difference here is that viewers witness the process of how Vito transforms himself to convey power, even if it is just to frighten his grandson for a brief moment.

Chasing his grandson through the tomato vines, Vito removes his orange peel fangs —and tellingly, it is at this moment that he erupts into the coughing fit that results in his collapse. Playing pretend with his grandson has been too much of a physical strain on his body; Vito gives up his monster act, and gives up the ghost. Likewise, Vito’s performance of power as Don has been the ultimate exertion in his life. He has structured his whole life and family around the power and persona of Don Corleone, and the toll ends up being too much to handle: Vito crumbles and falls in the tomato garden. He lies on the ground, next to the ripe, or possibly overripe, tomatoes that have burdened the vine branch with their own weight and have fallen to litter the soil.

Chasing his grandson through the tomato vines, Vito removes his orange peel fangs —and tellingly, it is at this moment that he erupts into the coughing fit that results in his collapse. Playing pretend with his grandson has been too much of a physical strain on his body; Vito gives up his monster act, and gives up the ghost. Likewise, Vito’s performance of power as Don has been the ultimate exertion in his life. He has structured his whole life and family around the power and persona of Don Corleone, and the toll ends up being too much to handle: Vito crumbles and falls in the tomato garden. He lies on the ground, next to the ripe, or possibly overripe, tomatoes that have burdened the vine branch with their own weight and have fallen to litter the soil.

At the very moment of Vito’s death, Coppola notably cuts to a more distant shot. The camera frames the tomato garden at the center of the backyard; in the confines of the garden lies Vito’s body. The image of Vito resting on the soil, the foundation of the garden, resonates with Vito’s role as the foundation of his family and business. He has worked and exerted himself completely to maintain the growth of his personal and family legacy. As a result, like the ripe tomatoes that must fall to make room for new ones, Vito must fall in order to make room for the new Don, his son.

At the very moment of Vito’s death, Coppola notably cuts to a more distant shot. The camera frames the tomato garden at the center of the backyard; in the confines of the garden lies Vito’s body. The image of Vito resting on the soil, the foundation of the garden, resonates with Vito’s role as the foundation of his family and business. He has worked and exerted himself completely to maintain the growth of his personal and family legacy. As a result, like the ripe tomatoes that must fall to make room for new ones, Vito must fall in order to make room for the new Don, his son.

There’s a sense that, even as this scene portrays the death of Vito Corleone, it also encapsulates his life. Vito has done everything in his power to plant, care for, and grow the seeds of his personal and business life. By laying the foundation for his generation and the generations to come after him, he has become the foundation. Coppola gives us as viewers five seconds to hear the wind and the birds chirping so that we register that this is a natural death — one that, for all its sadness, completes a cycle.

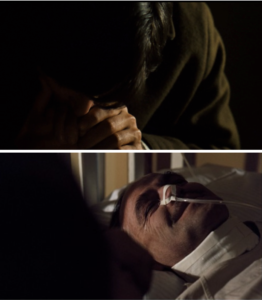

We hear a simultaneous scream, made more unsettling by its deepness, and by our awareness that it comes from a grown man who cannot suppress the anguish of his pain. And just like that, without warning, we are ejected at once from the scene’s mellow, easygoing tempo to one of fast-paced horror. By the time the garrote is placed around Brasi’s throat by an unknown assailant, we want Luca to overpower him, to use brute strength or even his gun to turn the outcome around. Ultimately, we just want his suffering to stop.

We hear a simultaneous scream, made more unsettling by its deepness, and by our awareness that it comes from a grown man who cannot suppress the anguish of his pain. And just like that, without warning, we are ejected at once from the scene’s mellow, easygoing tempo to one of fast-paced horror. By the time the garrote is placed around Brasi’s throat by an unknown assailant, we want Luca to overpower him, to use brute strength or even his gun to turn the outcome around. Ultimately, we just want his suffering to stop.

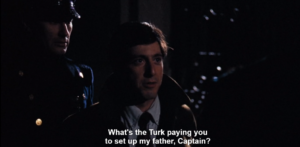

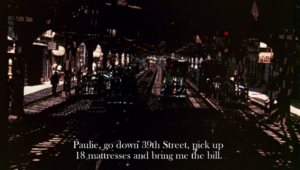

The transition to the scene establishes an atmosphere of tension. Two unidentified men drive Michael into the city to meet Kay at the hotel. The camera jump-cuts from a shot of Michael in the backseat to the car’s bumper. We watch the car pass a flashing yellow streetlight on its right side. It is nighttime, the road is clear, and the only sound effects we hear are the tires hissing against the asphalt. This shot lasts only twelve seconds but establishes a sequence and tone. The direct sound of the tires seems menacing and heightens the peril of events so far—Vito Corleone’s attack, Paulie Gatto’s assassination.

The transition to the scene establishes an atmosphere of tension. Two unidentified men drive Michael into the city to meet Kay at the hotel. The camera jump-cuts from a shot of Michael in the backseat to the car’s bumper. We watch the car pass a flashing yellow streetlight on its right side. It is nighttime, the road is clear, and the only sound effects we hear are the tires hissing against the asphalt. This shot lasts only twelve seconds but establishes a sequence and tone. The direct sound of the tires seems menacing and heightens the peril of events so far—Vito Corleone’s attack, Paulie Gatto’s assassination. A slow dissolve transitions us into the hotel room and is joined with a sound bridge, Irving Berlin’s “All My Life.” This song—a slow-tempo ballad often performed by a female vocalist addressing her lover—presents a surprising counterpoint to the preceding events, easing us into the scene and suggesting an emotional uplift in the narrative. It overlaps with the dialogue and is part of the film’s diegesis: the song seems to play somewhere in the background. The music is muted and subtle, softly complementing the dinner’s romantic atmosphere—a small round table and white tablecloth; red wine and steak; Kay’s lipstick-red blouse with a sweetheart neckline and puffed sleeves, Michael’s oxford shirt and tie. A lamp in the corner provides diffused light that illuminates Kay’s face. Her cheeks look cherubic; her skin, soft and warm.

A slow dissolve transitions us into the hotel room and is joined with a sound bridge, Irving Berlin’s “All My Life.” This song—a slow-tempo ballad often performed by a female vocalist addressing her lover—presents a surprising counterpoint to the preceding events, easing us into the scene and suggesting an emotional uplift in the narrative. It overlaps with the dialogue and is part of the film’s diegesis: the song seems to play somewhere in the background. The music is muted and subtle, softly complementing the dinner’s romantic atmosphere—a small round table and white tablecloth; red wine and steak; Kay’s lipstick-red blouse with a sweetheart neckline and puffed sleeves, Michael’s oxford shirt and tie. A lamp in the corner provides diffused light that illuminates Kay’s face. Her cheeks look cherubic; her skin, soft and warm.

The halting rhythm of the camera draws out the scene’s feeling of awkwardness. The scene’s establishing shot shows Kay sitting at the dinner table. The camera frames her using a point-of-view vantage and positions us in a medium close-up. Immediately we notice her red blouse, princess-length pearl necklace, coiffed hair, and hesitant face. Kay appears vulnerable, and since that vulnerability charges the establishing shot, we know it will inform the scene. The camera transitions to Michael wadding his napkin, looking down and avoiding eye contact with Kay.

The halting rhythm of the camera draws out the scene’s feeling of awkwardness. The scene’s establishing shot shows Kay sitting at the dinner table. The camera frames her using a point-of-view vantage and positions us in a medium close-up. Immediately we notice her red blouse, princess-length pearl necklace, coiffed hair, and hesitant face. Kay appears vulnerable, and since that vulnerability charges the establishing shot, we know it will inform the scene. The camera transitions to Michael wadding his napkin, looking down and avoiding eye contact with Kay. We end with a shot of Kay staring at her wine glass. The camera once again positions us at a medium close-up, reinforcing her pain and hesitation. We know Sollozzo’s attack has unnerved Michael. We might foresee his looming retaliation. Perhaps we even correctly infer his ultimate fate from these character developments. But empathizing with Kay’s pain, we question if her relationship with Michael will last.

We end with a shot of Kay staring at her wine glass. The camera once again positions us at a medium close-up, reinforcing her pain and hesitation. We know Sollozzo’s attack has unnerved Michael. We might foresee his looming retaliation. Perhaps we even correctly infer his ultimate fate from these character developments. But empathizing with Kay’s pain, we question if her relationship with Michael will last.

Early in the opening wedding scene of The Godfather, a photographer lines up the Corleone family, preparing a family photo to solemnize the marriage of Constanzia, or Connie, Corleone to Carlo Rizzi. Yet Vito Corleone, the Don of this Sicilian family, notes his youngest son’s absence and so stops the shot from being taken: “We’re not taking the picture without Michael.” A picture is forever, and Vito—the center of the family, and with an especially soft spot for his son Michael—insists that all must be present and all must be willing to play their part. What Vito has created through the Corleone family is represented in its purest and most picturesque form by Connie’s wedding, which is huge, vibrant, and cheerful.

Early in the opening wedding scene of The Godfather, a photographer lines up the Corleone family, preparing a family photo to solemnize the marriage of Constanzia, or Connie, Corleone to Carlo Rizzi. Yet Vito Corleone, the Don of this Sicilian family, notes his youngest son’s absence and so stops the shot from being taken: “We’re not taking the picture without Michael.” A picture is forever, and Vito—the center of the family, and with an especially soft spot for his son Michael—insists that all must be present and all must be willing to play their part. What Vito has created through the Corleone family is represented in its purest and most picturesque form by Connie’s wedding, which is huge, vibrant, and cheerful. In the first shot following Vito’s dealings with Amerigo Bonasera, we glimpse the throng that has assembled for the event: though a tree covers half of the crowd, there are still dozens of visible people milling around, and by placing the camera far from the event, the individual people become a blur and turn into one huge sea of costumed bodies. The image suggests how, to the Corleones, a family should function: though the individuals that make up the larger family business are essential to its workings, they are all under the guise of one group and so are united by that group. Even with a sizable attendance already inside the estate, people can be seen still walking into the courtyard. Everyone, from tiny toddlers to their aging grandparents, must come and pay respects to Connie in this momentous event.

In the first shot following Vito’s dealings with Amerigo Bonasera, we glimpse the throng that has assembled for the event: though a tree covers half of the crowd, there are still dozens of visible people milling around, and by placing the camera far from the event, the individual people become a blur and turn into one huge sea of costumed bodies. The image suggests how, to the Corleones, a family should function: though the individuals that make up the larger family business are essential to its workings, they are all under the guise of one group and so are united by that group. Even with a sizable attendance already inside the estate, people can be seen still walking into the courtyard. Everyone, from tiny toddlers to their aging grandparents, must come and pay respects to Connie in this momentous event. Yet Vito is not just a man who spends a lot of money to make his daughter’s wedding a great celebration; he’s the sort of father who actively shows his care with that money by partaking in the festivities, spending time with his family throughout despite his ongoing business deals behind the scenes. This scene fills the wedding with his attention and care as he dances with his wife in the midst of the crowd. Smiles on their faces, the couple waltz as Vito makes an inaudible comment to his wife that conveys the couple’s agreeable intimacy.

Yet Vito is not just a man who spends a lot of money to make his daughter’s wedding a great celebration; he’s the sort of father who actively shows his care with that money by partaking in the festivities, spending time with his family throughout despite his ongoing business deals behind the scenes. This scene fills the wedding with his attention and care as he dances with his wife in the midst of the crowd. Smiles on their faces, the couple waltz as Vito makes an inaudible comment to his wife that conveys the couple’s agreeable intimacy. This scene is mirrored again at the end of the wedding: Vito leads his daughter through the crowd of clapping attendees, clutching her hand tightly. Holding hands is a sign of affection often seen between a parent and a young child, and in this context the meaning is still valid—perhaps even more so due to Connie’s older age and the likelihood that they no longer are so physically close. As Vito carefully lays his hand on her waist and they begin to waltz, Connie speaks inaudibly to him, causing them both to smile. When the scene cuts to a shot farther away from the two, Connie hugs him tightly as they continue their waltz. This increased physical affection suggests their own emotional intimacy, which they unabashedly display on stage.

This scene is mirrored again at the end of the wedding: Vito leads his daughter through the crowd of clapping attendees, clutching her hand tightly. Holding hands is a sign of affection often seen between a parent and a young child, and in this context the meaning is still valid—perhaps even more so due to Connie’s older age and the likelihood that they no longer are so physically close. As Vito carefully lays his hand on her waist and they begin to waltz, Connie speaks inaudibly to him, causing them both to smile. When the scene cuts to a shot farther away from the two, Connie hugs him tightly as they continue their waltz. This increased physical affection suggests their own emotional intimacy, which they unabashedly display on stage. Instead of greeting Michael with care and love—as Tom Hagen does when he first sees Michael, and as an older brother should do after not having seen his younger brother in quite some time—Fredo flicks the back of Michael’s head. While this gesture suggests a kind of playful intimacy, it underscores Fredo’s immaturity and inability to socialize with people in a more dignified way. The blocking of the action in the scene—with Fredo kneeling between Michael and Kay—also conveys his awkwardness and divisiveness. Michael’s act of bringing Kay to the wedding shows his devotion to her and telegraphs that one day, they too might get married. When Fredo sits between them, he separates the two and effectively disrupts the natural state of the couple.

Instead of greeting Michael with care and love—as Tom Hagen does when he first sees Michael, and as an older brother should do after not having seen his younger brother in quite some time—Fredo flicks the back of Michael’s head. While this gesture suggests a kind of playful intimacy, it underscores Fredo’s immaturity and inability to socialize with people in a more dignified way. The blocking of the action in the scene—with Fredo kneeling between Michael and Kay—also conveys his awkwardness and divisiveness. Michael’s act of bringing Kay to the wedding shows his devotion to her and telegraphs that one day, they too might get married. When Fredo sits between them, he separates the two and effectively disrupts the natural state of the couple. Though Sonny Corleone, the oldest son and therefore the eventual successor to the family business, shares few of Fredo’s character traits, he is also unlike his father in both personality and values. His reckless and impulsive nature is dramatized in his interaction with the FBI agents who are documenting, in an act of surveillance, the people who are attending the wedding. After unsuccessfully attempting to get the agents to leave and being met instead with a stoic face and an FBI ID, Sonny takes his frustration out on one of the agents, yanking his camera away and throwing it on the ground. Afterwards, he’s held back by Peter Clemenza; if Clemenza had not been there, Sonny would have likely thrown some punches. Then, in classic gangster fashion, he drops a couple of crumpled bills on the ground to pay for the broken camera.

Though Sonny Corleone, the oldest son and therefore the eventual successor to the family business, shares few of Fredo’s character traits, he is also unlike his father in both personality and values. His reckless and impulsive nature is dramatized in his interaction with the FBI agents who are documenting, in an act of surveillance, the people who are attending the wedding. After unsuccessfully attempting to get the agents to leave and being met instead with a stoic face and an FBI ID, Sonny takes his frustration out on one of the agents, yanking his camera away and throwing it on the ground. Afterwards, he’s held back by Peter Clemenza; if Clemenza had not been there, Sonny would have likely thrown some punches. Then, in classic gangster fashion, he drops a couple of crumpled bills on the ground to pay for the broken camera. This moment from the wedding scene encapsulates well the cruelty of the irony. His wife is in the foreground, busy talking to other guests and joking about the size of his phallus—which in its own way is a form of endearment. Meanwhile Sonny is almost directly behind her, just having whispered into the bridesmaid’s ear to meet him in a more private setting. He is cheating on his wife literally behind her back, and her close proximity to him while he commits this act suggests how normal this sort of betrayal has become for him. He puts a little care into hiding his unfaithfulness, but his suspicious activities are not unnoticed by his wife, who looks behind her to find him, only to see that he is already gone.

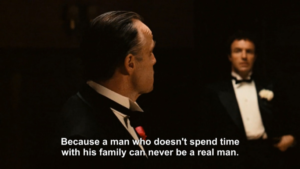

This moment from the wedding scene encapsulates well the cruelty of the irony. His wife is in the foreground, busy talking to other guests and joking about the size of his phallus—which in its own way is a form of endearment. Meanwhile Sonny is almost directly behind her, just having whispered into the bridesmaid’s ear to meet him in a more private setting. He is cheating on his wife literally behind her back, and her close proximity to him while he commits this act suggests how normal this sort of betrayal has become for him. He puts a little care into hiding his unfaithfulness, but his suspicious activities are not unnoticed by his wife, who looks behind her to find him, only to see that he is already gone. While talking to Johnny Fontane, he asks him if he spends time with his family, which Johnny replies affirmatively to. He follows up with a bit of moral instruction—“Because a man who doesn’t spend time with his family can never be a real man”—and here he looks directly at Sonny, directing the line more to him than to Johnny. Vito doesn’t address the issue in a private one-on-one, but he doesn’t need to, as this line serves as his condemnation of Sonny’s act. And in this condemnation, he embarrasses his son for failing to be a “real man” and a proper Corleone father.

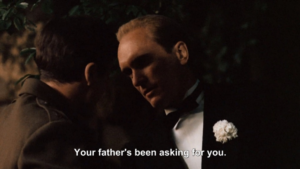

While talking to Johnny Fontane, he asks him if he spends time with his family, which Johnny replies affirmatively to. He follows up with a bit of moral instruction—“Because a man who doesn’t spend time with his family can never be a real man”—and here he looks directly at Sonny, directing the line more to him than to Johnny. Vito doesn’t address the issue in a private one-on-one, but he doesn’t need to, as this line serves as his condemnation of Sonny’s act. And in this condemnation, he embarrasses his son for failing to be a “real man” and a proper Corleone father. While Michael may not be as immature as his two older brothers, the moment he walks into the wedding a distinction is already made between him and the rest of his family. As he walks into the estate with Kay, noticeably late—13 minutes already into the film to be exact—his military uniform sticks out like a sore thumb. Michael makes deliberate choices to differentiate himself from the rest of the Corleone family, showing up when he wants to instead of at the beginning of the wedding, wearing what he wants to instead of a tuxedo like the rest of his brothers, and bringing a non-Italian-American date (who herself chooses to wear a dress that is Americana in style). These choices construct his character as just another attendee and not a central member of the Corleone family. In his first interaction with a member of the family, Michael hears from Tom that his father is looking for him.

While Michael may not be as immature as his two older brothers, the moment he walks into the wedding a distinction is already made between him and the rest of his family. As he walks into the estate with Kay, noticeably late—13 minutes already into the film to be exact—his military uniform sticks out like a sore thumb. Michael makes deliberate choices to differentiate himself from the rest of the Corleone family, showing up when he wants to instead of at the beginning of the wedding, wearing what he wants to instead of a tuxedo like the rest of his brothers, and bringing a non-Italian-American date (who herself chooses to wear a dress that is Americana in style). These choices construct his character as just another attendee and not a central member of the Corleone family. In his first interaction with a member of the family, Michael hears from Tom that his father is looking for him. Coppola cuts to a close-up shot here, placing emphasis on both the importance of the statement as well as the secrecy of it—as it is family business—to ensure that Kay will not overhear. But Michael barely reciprocates, simply nodding before sitting back down to continue dining with Kay. This is a direct rejection of Vito, and more generally a rejection of any effort to craft stronger ties with his family and the dubious business they deal in.

Coppola cuts to a close-up shot here, placing emphasis on both the importance of the statement as well as the secrecy of it—as it is family business—to ensure that Kay will not overhear. But Michael barely reciprocates, simply nodding before sitting back down to continue dining with Kay. This is a direct rejection of Vito, and more generally a rejection of any effort to craft stronger ties with his family and the dubious business they deal in. Michael’s decision to create a strong distinction between himself and his family is epitomized in a later scene in which he recounts the story of how Vito helped launch Johnny’s solo career. As he relates Vito’s criminal activities to Kay in vivid detail, he ends with the line “That’s my family Kay. It’s not me.” Michael makes it clear to Kay that he no longer feels a sense of belonging within his own family. It appears that Michael, decked out in his military uniform, is attempting to rebrand himself as a law-abiding, patriotic citizen — the exact opposite of a Corleone.

Michael’s decision to create a strong distinction between himself and his family is epitomized in a later scene in which he recounts the story of how Vito helped launch Johnny’s solo career. As he relates Vito’s criminal activities to Kay in vivid detail, he ends with the line “That’s my family Kay. It’s not me.” Michael makes it clear to Kay that he no longer feels a sense of belonging within his own family. It appears that Michael, decked out in his military uniform, is attempting to rebrand himself as a law-abiding, patriotic citizen — the exact opposite of a Corleone. Furthermore, we can see that, outside of his decisions to distance himself from the family, Michael is still a bearer of Sicilian values and culture: he talks about Sicilian family titles, recounts stories regarding his father, and even waltzes with his significant other, much like Vito is seen doing at various points in the wedding.

Furthermore, we can see that, outside of his decisions to distance himself from the family, Michael is still a bearer of Sicilian values and culture: he talks about Sicilian family titles, recounts stories regarding his father, and even waltzes with his significant other, much like Vito is seen doing at various points in the wedding.