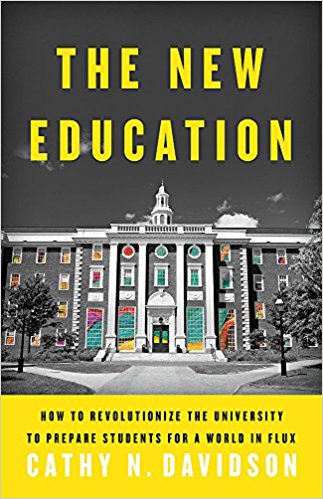

This website exists because, in the fall of 2017, I read the following sentences from Cathy Davidson’s The New Education, a book-length manifesto for rethinking how universities teach their students: “Students do not do particularly well writing papers for the sake of writing papers,” Davidson suggests,  referring to a landmark Stanford study of how the digital landscape has altered the practice of writing and the sensibilities of younger writers. “Rather, students value writing that ‘makes something happen in the world.'” (93)

referring to a landmark Stanford study of how the digital landscape has altered the practice of writing and the sensibilities of younger writers. “Rather, students value writing that ‘makes something happen in the world.'” (93)

Davidson’s point aligned with my own recent experience as a teacher, and specifically as a teacher of writing. I’d started to feel a sense of diminishing returns when I simply asked students to produce what has long been the “industry standard” in English departments: the five-page essay of close analysis. At its best, this assignment allowed students to shine new light on a formerly obscure corner of a text (and prove to themselves that they were ready for the rigors of graduate study in the discipline). At its worst, this assignment felt like make-work to students — something written only for the eyes of the person grading their writing. It was inconceivable, to many, that anyone else might be interested in their thoughts on, say, Emily Dickinson or Robert Louis Stevenson or Toni Morrison. They were writing an essay because they had to, for someone who was reading it because he had to—not exactly a recipe for the production of deathless prose.

So in 2016-17, I taught two new courses for me: a creative nonfiction workshop in Cal’s English Department and an honors research seminar on the 1970s Bay Area for Cal’s American Studies Program. In both classes, the goal for the students was to create something that, after multiple revisions, would be published online — something written “for the world”. In the creative nonfiction workshop, which had twelve students, the platform was a Medium site called The Annex; individual pieces came to attract somewhere between a hundred and 9,000 views. In the research workshop, which had only eleven students, the class collaborated to create a digital history project, The Berkeley Revolution, which, upon its launch in July 2017, received favorable notice across the web and has drawn a steady stream of about 50 unique visitors a day.

I had experienced some success in turning undergrad seminars into publication workshops, but reading The New Education made me wonder: would it be possible to do something similar with a lecture course?

I had experienced some success, then, in turning undergrad seminars into publication workshops, but reading The New Education made me wonder: would it be possible to do something similar with a lecture course, and one not specifically oriented to writing? In the spring of 2018, I was set to teach a “Literature and History” lecture course on the 1970s. I decided to enlist the forty-plus students in the class in a writing experiment, and to make the course’s reader—Joshua Anderson, the Cal grad student assigned to assist with the grading—my collaborator in the editorial enterprise.

Generating the Assignment: “Fifty Ways of Looking at The Godfather”

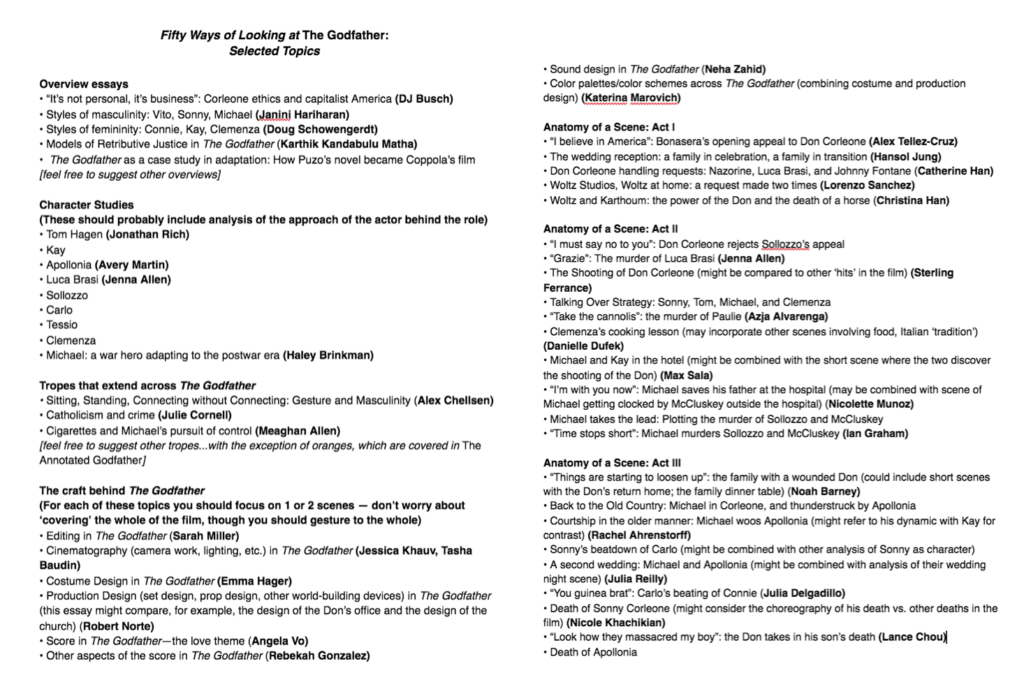

Good news for those who might wish to adapt this project for their own purposes but are leery of anything that smacks of technophilia: the writing assignment that generated this site bore great resemblance to the one I’d used in previous versions of my course—a “close passage analysis” assignment. (In fact, the model essay I gave students, which appears here as “Inhale/Exhale: Cigarettes and the Power of Michael Corleone,” had been written for the Fall 2016 version of the course.) The frisson, such as it was, came from the assignment’s framing. From the start, students knew that they were working together on a larger project— “Fifty Ways of Looking at The Godfather: A Collective Project in Close Film Analysis”—with their essay but one piece in a larger puzzle. I had chosen The Godfather as our point of focus because (a) it was epic, multi-dimensional, and exquisitely crafted, so could easily be parsed from 50-plus different angles; and (b) as an early-1970s artifact, it fell early in the term on the syllabus, so on a practical level we could have two months to develop the larger project.

Here’s some language from the original assignment:

The Godfather is an intricately crafted film that has little wasted motion to it: even its seemingly minor scenes, and seemingly minor characters, add to its textured portrait of the Corleone family and its ‘family business.’

Through this assignment, we will throw ourselves collectively into the project of figuring out how the many different pieces of The Godfather add up. Each one of you will take on a different aspect of the film and write an essay that—if appropriate—blends interpretation and some research into the film through reference to the two major sources on its making, The Annotated Godfather and The Godfather Notebook.

Your essay topics will draw from the list of topics posted in a google doc, though you are free to suggest additional topics of interest.

Because the essays will be published digitally, you are asked to be aware of the possibilities of the digital format. It is expected that, in your close analysis of the film, you will stitch in a number of screenshots—or possibly .gifs—as you home in on key moments in the material you’ve selected to analyze.

You should also be aware that you are writing for a larger audience. Imagine yourself explaining the workings of the film to a sophisticated but not necessarily expert reader—someone who has watched The Godfather, is aware of the basics of film technique, and wants to understand better the workings of the film. Amy Taubin’s book on Taxi Driver might give you an example of the right tone: smart, vivid, concise, light on its toes even when engaging with weighty matters. Try to write something that will be both stimulating and useful to the person reading it.

To ensure that students wrote on distinct topics—I didn’t want half the class to write on the baptism/assassination montage, as captivating as it is—I generated fifty-plus topics and created a google doc so that students could see the menu of options and claim a topic. Around seven of the forty-five students took the initiative to devise their own topics (for instance, the essays here on alcohol, body language, and color accents). I encouraged students with special areas of expertise to tackle topics that would draw on that expertise. A student with a longstanding interest in fashion took on costume design; a student who edits Cal’s music magazine, the film’s score.

A Process of Writing and Revision: From 45 Rough Drafts to 45 Final Drafts

My strong sense was that my students, as talented as they were, could write pieces on The Godfather that invited general interest only if they did what professional writers do: revise their pieces through a sustained dialogue with editors who could help them tighten their prose and put their finger on what was most compelling in it. This meant that these pieces would not be produced on the usual undergraduate timetable—submission and evaluation within a span of, say, one or two weeks. Rather, there would be a six-week recursive process of feedback and revision, with first drafts submitted in mid-March.

This focus on revision created a labor problem, since giving good, specific feedback on writing is a labor-intensive endeavor that, as far as I know, no app has managed to simulate. I crowd-sourced that labor, in part, by carving out one class day for peer workshops, with each student paired up with one other student so that they could get, and give, intensive feedback.

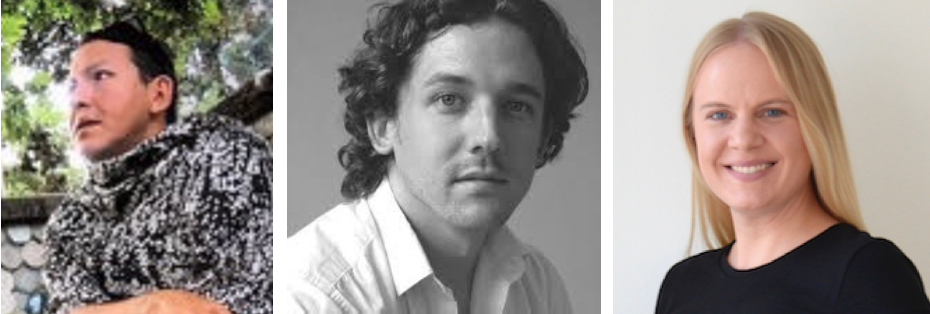

More significantly, I recruited Kyler Ernst, a talented undergraduate from my fall creative nonfiction workshop, to help with the fine-grained work of commenting on and line-editing the students’ essays. (This hire was supported by Cal’s Art of Writing Program, through the good offices of Professor Ramona Naddoff.) Kyler, Joshua and I divvied up the 45 rough drafts between the three of us.

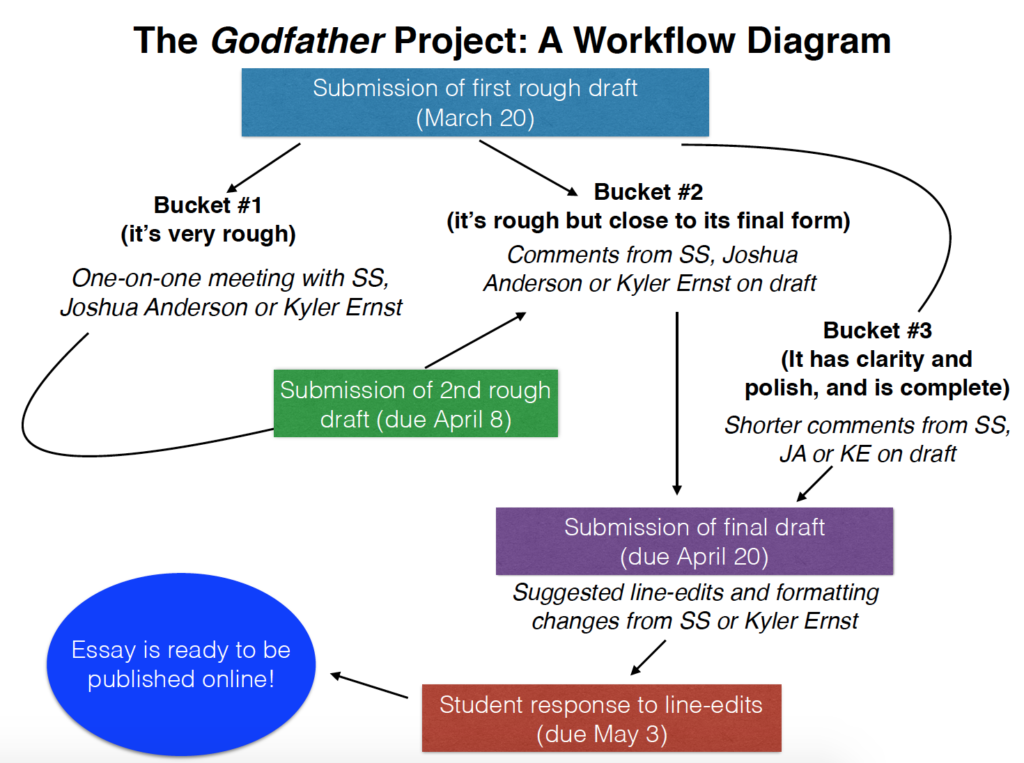

Not long after we dove into reading the students’ drafts, we discovered that it made no sense to give the same sort of feedback on every draft. Some drafts were exceptionally “drafty”—unfinished, or not well-organized, or still in search of a central argument. Others were already polished to a fine degree, and could be line-edited in preparation for inclusion on the site. Still others—the majority—fell in the middle: they were coherent, but needed considerable work so that their promise might be realized.

The students who’d written “drafty” drafts were enjoined to meet with me, Joshua, or Kyler, and asked to turn around a second draft quickly if they wished to have their work under consideration for the final site. The other students (about 3/4 of the class) had their drafts edited through the “Track Changes” function on Microsoft Word, and then had several weeks to respond to comments and revise accordingly. Final drafts were submitted on April 20, one month after the due date of the first rough draft.

Tough Calls: From 45 Final Drafts to 17 Final Pieces

With these 45 final drafts in hand, Kyler, Joshua and myself met to determine which pieces might go forward and be further line-edited so as to appear on the site. We were happy to see how much, in general, the essays had improved: they were more focused, more sure-footed, and more sensitive in their handling of the details of the film. We were also aware that time was ticking, that the end of the semester was nigh, and that it was unfeasible for Kyler and myself (Joshua was going to be busy with the evaluation of the students’ take-home finals) to line-edit more than around fifteen essays by the end of the term.

Winnowing the pile of essays from 45 to a third of that number was not an easy task. We started by observing that despite our best efforts, some essays had repeated some of the same material, and we could make some progress by determining, say, which essay had a more nuanced take on Clemenza and his cannolis. Ultimately, too, it seemed that the students who focused on technical aspects of The Godfather—its handling of editing, its production or costume design, its camera work—were more successful at finding a fresh angle on the film. Finally, we put a strong value on the crispness of prose: a tight 1000-word essay was easier to imagine on the site than a 2000-word essay, studded with rich insights, that had some soft spots to it. We ended up choosing seventeen essays, the large majority of which I took responsibility for line-editing.

Designing the Site and Fine-Tuning Its Design

At this point our story takes a happy turn. The process of creating this site reminded me of my experience seeing an apartment building go up in my neighborhood: for years, there was little discernible progress as the foundation was laid and the scaffolding erected—and then, seemingly in the blink of an eye, there was a clean, habitable structure with doors, windows, and all the architectural trimmings. So with this site: after the two months of labor-intensive writing and re-writing, editing and line-editing, the site itself came together swiftly over a few weeks, in the form you now experience.

I was fortunate to have hired the very capable Kristin Jones, a web developer and Germanist who had earlier designed my Berkeley Revolution site, to design the site; Kristin quickly tailored the Fox WordPress Theme (cost: $59) so that it matched what we needed. Kyler—who happily also had a background in graphic design—created the header banner and the footer banner. I inputted the essays and formatted them with images, block quotes, and the like. The process was relatively frictionless.

In retrospect, it seems to me that the most difficult work behind the site involved the part that now is relatively invisible. This was the mental work that my students performed by writing and rewriting their prose, and that I and my fellow editors performed through the various tasks of line-editing—hacking away at unnecessary verbiage or making suggestions for how an argument could take on an extra edge. Notably, this is also the part of the site that teachers in the humanities tend to be extremely qualified to pull together and pull off.

Some visitors to the site may appreciate that the site is visually attractive too—and I would welcome any such appreciation. But I would underline, for any teachers who balk at creating a public-facing digital project, that the software developers of the world have risen to the challenge of developing easily-customized templates for digital publishing. These teachers should know that orchestrating the design side—the nifty sidebars and widgets, the clean lines and coordinated fonts—has been made easy. As ever, the prose’s the thing.